A history of global feminisms

Richard B. Wolf Associate Professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality

- The history of global feminisms is linked to the histories of slavery and colonialism.

- The systematic exclusion of women of colour shows that the category of “woman” is never just about women.

- The emergence of feminist coalitional politics in the 1970s continues to be influential today.

Origins of global feminism

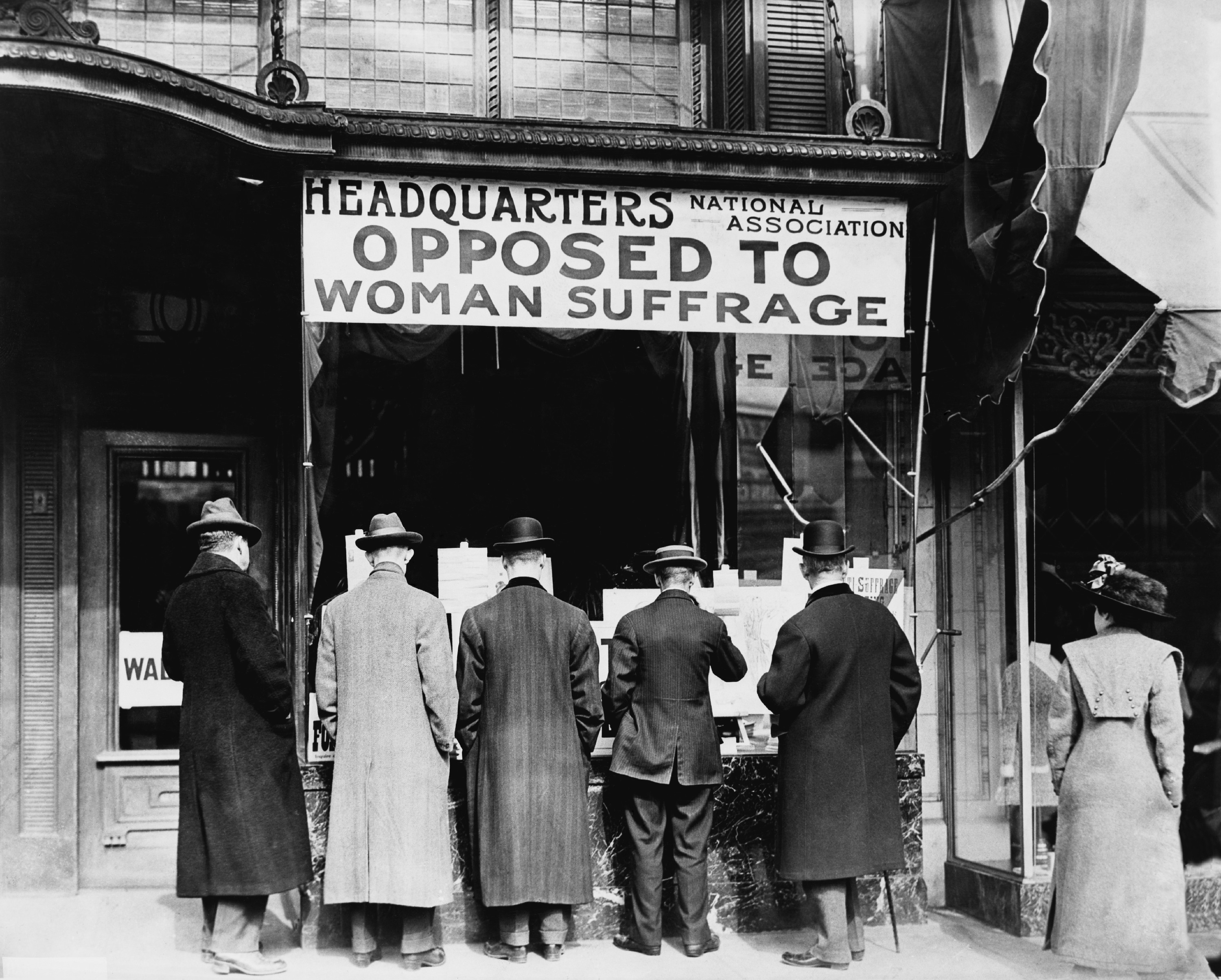

© Photo by Everett collection

The history of global feminisms is deeply entrenched in the history of colonialism and the history of the rise and fall of slavery in the 19th century. In the first place, the origins of women’s movements begin in the 19th century – although women fighting for citizenship rights, the right to vote, and the right to have a voice in political and social life, happens long before then. But it’s in the 19th century that we see the emergence of long-term, wide-scale political movements where women make a claim to the right to vote and the right to citizenship in a broader sense. These rights and ideas cannot be disassociated from the end of slavery and the rise of colonialism in many parts of the world.

Why should we think about the origins of global feminisms with these complicated histories? The abolition of slavery gives us the first and most comprehensive language about humanism, equity in humanistic imaginations, and how we can imagine each other as humans. In particular, it gives us a language about how we can think about those people who have been treated as less than human, especially women, as part of and critical to political and social movements.

Decolonisation and feminism

The history of colonialism gives women political access. White women in metropole spaces, such as London or North America, who are part of the abolition movements against slavery also become critical to the project of empire. Their work to fight for women’s rights to vote and women’s rights to determine the destiny of empire is intricately tied to their ideas about womanhood. It’s hard to think about the history and the origins of global feminism without thinking about the racial logic of slavery and colonialism in the making of feminism itself.

In the 20th century, we see political movements transform. The process of decolonisation and the end of systems like Jim Crow create the possibility of feminist movements all over the world, not only in the metropole and in white-only spaces. And it’s in the political movements against slavery and segregation in the context of the United States, or in movements for the end of colonialism in places like India and sub-Saharan Africa, that we see movements for women’s rights and the articulations about the necessity for women to participate wholly as citizens within a society.

Decolonisation and feminism are thus inextricably linked. Decolonisation is about the end of the subordination of people, and feminist thought is a critique of the subordination of women in relation to structures of patriarchy. In the early 20th century, women who are part of nationalist movements all over the colonial world make arguments about the failure of the promise of colonialism: the promise of liberation, humanism, and the uplift of people of the colonial world. That critique pivoted on the idea that women should have equal rights, equal citizenship, because they, in fact, had the most capacity to be human. Women’s participation in the project of decolonisation is essential.

Women’s movements in the colonial world

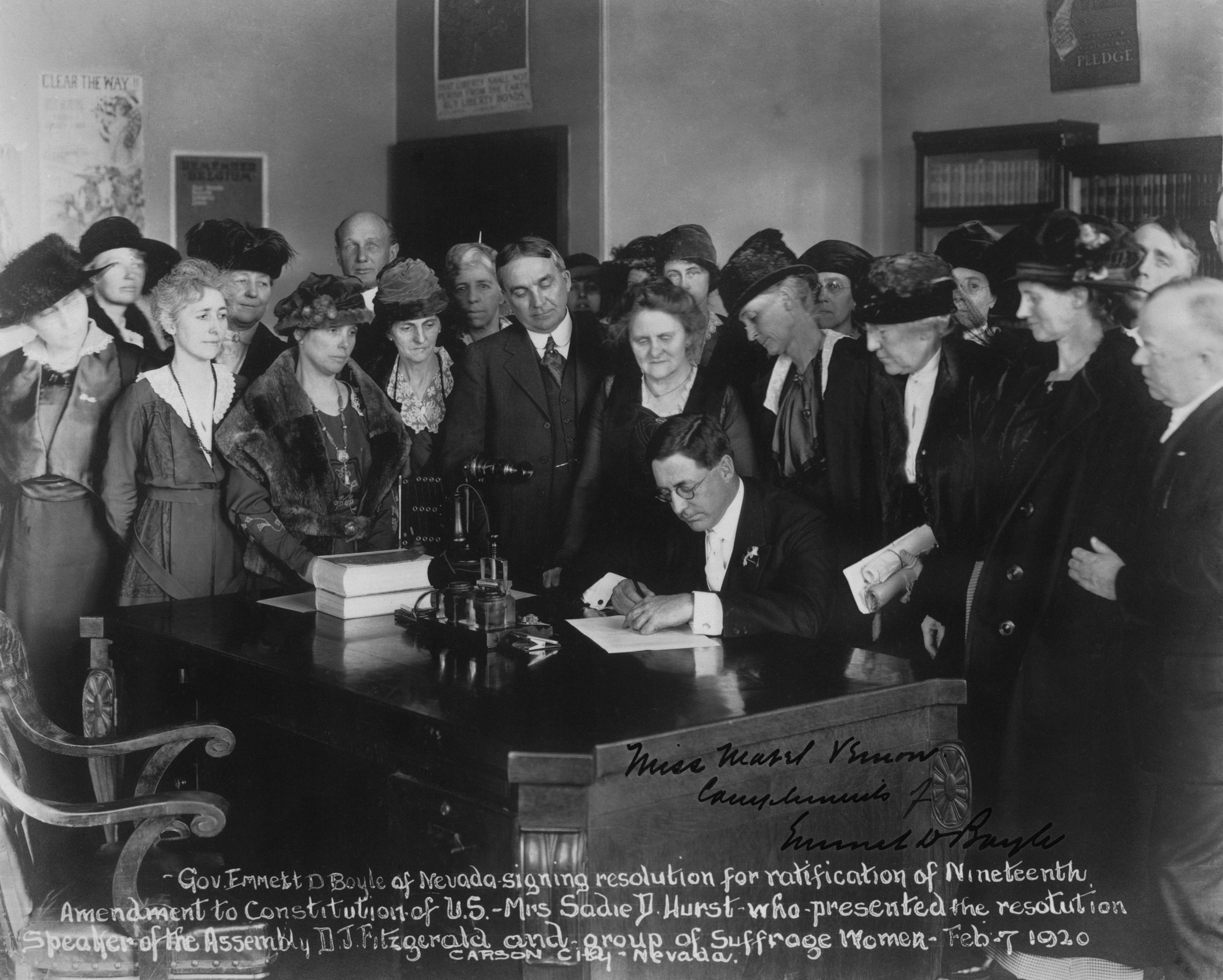

© Photo by Everett collection

The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment in the United States. That’s one hundred years of women having the right to vote. But it would be inappropriate to think of the Nineteenth Amendment as the only place where women’s suffrage movements happened.

Ideas about women having the right to vote happen all over the world from the end of the 19th century, particularly in the colonial world. Most of the people of the world through the beginning of the 20th century were denied the right to vote because they were colonised. We see the convergence of women making claims of the right to vote in places like India, with broader claims about decolonisation and people having sovereignty over themselves.

In India, as early as the 19th century, women begin writing memoires, political texts and science fiction, articulating ideas about social reform and the rights of women. And at the turn of the century, we see Indian women travelling the world. Pandita Ramabai, an educated woman, toured the world to make an argument about the rights of women in India. Those political and social ideas come from social reform movements that are happening in India as a result of colonialism.

Feminism in India

In some ways, the women’s movement in India responds directly to the problem of colonialism. When the British colonial state came to India, one of the hallmarks of their critique of Indian society, and the ideas that they used to justify the colonisation of the people of South Asia, was the condition and the degradation of women. From the 19th century and into the early 20th century, we see a response by Indian women about their social degradation, the condition of women, the right to literacy, the right to education, the right to public space and public movement, and sexual desire. Those articulations are critical of both the colonial state and an entrenched patriarchy that emerges as a result of colonialism, as Indian men begin to take advantage of colonial structures to create patriarchal legal, political and economic structures for themselves.

By the early 20th century, Indian women are leading political movements against patriarchal structures, such as marriage laws, or laws that govern questions of gender violence, to argue that they should have rights, even if they did not have access to political and social domains. For example, in the early 1920s, women who were self-proclaimed sex workers or described as so-called prostitutes were part of Gandhian political movements. They believed that they had the right to public space. There is a paradox as people like sex workers, who do not fit normative ideas of what good womanhood is, participate in Gandhi’s political movement. Gandhi himself articulates politically complicated and often contradictory ideas about what he thinks women should be. He often had normative ideas about women in their sexuality. He tries to dissuade women who are sex workers from participating in his political movement, even though it was supposed to be an inclusive de-colonial movement.

The Constitution of India and women’s rights

By the 1930s and 1940s, there are large, structured, formally organised wings of women who participate in the nationalist movement and become part of the major political parties like the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress. These major political parties then come to take over when India and Pakistan declare independence in August 1947.

In those political debates about what an Indian constitution should be, there are women participating, although not in significant numbers. There are people who argue that citizenship should be for all and that women should not have any affirmative action programmes, or what was called “reservations”, to determine specialised citizenship for them. The idea is that the right to vote and the right to participate politically should be accessible to all, and there should not be any specialised programmes to facilitate women coming into political office or political life. This has mixed results.

In 1947, everyone in the new country called India gets franchise. We cannot say the same for places like the United States. In fact, the United States is not a full democracy until 1965 when the Voting Rights Act actually gives African Americans the right to vote. In some ways, the colonial space is full of progressive politics. Women get the right to vote early. And yet, at the end of the 20th century, there is limited access to political participation for all sorts of other reasons.

Systematic exclusion of women of colour

It’s important to think about the systematic exclusion of women of colour, and the persistence and the refusal of women of colour to accept limited access to citizenship. This includes suffrage claims in the 19th century, as well as events like the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in the context of the United States.

When the Nineteenth Amendment is passed in 1920, the Chinese Exclusion Act is created in the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act does not give rights of citizenship to anyone from Asiatic regions. In fact, these immigrants don’t have rights until many years after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. So, women of colour who were integral to the suffrage movement, including Chinese Americans and Native women in the United States who participated fully in the suffrage movement, did not have access to the right to vote despite the fact that there was a suffrage movement which pushed for it and the Nineteenth Amendment supposedly enfranchised women. This point shows why we cannot disaggregate the question of citizenship and the question of race from the question of gender and women’s rights.

The leadership of women of colour

© Photo by Talukdar David

2020 is the 100th anniversary of women getting the right to vote. And yet, it’s only white women who gained access to the right to vote. Thanks to the scholarship of many people, such as Martha Jones, we know that Black women have been essential to the construction of the suffrage movement and the women’s rights movement in the United States. As early as Harriet Tubman, we see the participation of Black women in suffrage movements. However, Black women are denied the right to vote until the 1965 Voting Rights Act. We see through this differential access that the category “woman” is never, in fact, just about women. Without an intersectional analysis that helps us think about racial difference, about the subordination of certain races and classes of people from access to the right to vote, it’s hard to think about women’s rights more broadly.

Women of colour take leadership in pushing against these limitations, from fighting Chinese exclusion to the 1960s civil rights movement and the 1965 Voter Act. But from the 1970s, women of colour begin to articulate other sites needing political movements, from women’s rights and access over their body to women’s critique of the carceral state. From the 1960s and 1970s, and through Angela Davis’s scholarship and political activism, we see that there is no way to think about womanhood without thinking about the particular conditions of women of colour – specifically, Black women –, for critiquing the experience of subordination in the United States.

Towards feminist coalitional politics

In the metropole, the women’s movement was never just one movement. It was always variegated. That difference and that conflict within women’s movements was essential for the development of feminist ideas, feminist theories and feminist political action over the course of the 20th century. In the 1970s, the fractioning of the women’s movement becomes most apparent. For example, the Third World Women’s Alliance emerges from civil rights organising led by Black women, which sees a coalitional politics based on intersectionality. It’s based on the idea that there is no way to disaggregate the condition of women from the condition of class, race and social difference. And without thinking about class, race and the critique of capitalism, there’s no way to think about the condition of women, womanhood and work in the United States.

The Third World Women’s Alliance was about creating alliances between women who had just decolonised in the colonial and post-colonial world with women of colour in the United States, especially immigrant women. Those coalitional politics, that expansive imagination of women of colour as a political idea, emerge in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly with the Combahee River Collective, which creates a statement in 1977 about the unique position of women of colour and Black women in articulating a politics.

Those ideas are fundamental for how we can think about feminist coalitional politics today. It is feminists that are leading political movements, and it is women of colour that are largely leading political movements that are still identifying problems that feminists identified in the 1970s, such as decolonisation and knowledge-making. Who has the right to create knowledge, whether it’s the media or scholars? What does it mean to disassemble structures of patriarchy and white supremacy and institutions? Those critiques began decades ago, and feminists continue to create those coalitional politics today.

Discover more about

Global feminisms

Mitra, D. (2020). Indian Sex Life: Sexuality and the Colonial Origins of Modern Social Thought. Princeton University Press.

Kaplan, C., & Mitra, D. (Hosts). (2019, March 29). Ask a Feminist: Soraya Chemaly Discusses Feminist Rage with Carla Kaplan and Durba Mitra [Audio podcast transcript]. In Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society.