Let me give one example: in the 14th century, Europe suffered bubonic plague, the Black Death, which killed up to half the population of many towns and villages, but the other half went on fatalistically. Now, if we had a pandemic which killed even 1% of the population, it would overwhelm hospitals and probably lead to a social breakdown because our expectations are so high. It’s perhaps ominous that COVID-19 has killed about 0.3% of the population in some European countries and in the United States, so 1% would be really catastrophic.

The vulnerabilities of civilisation on Earth and beyond

Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics

- If we think about the world in 2050, it’s going to be very important to ensure that inequalities are reduced.

- While there may be a few privately funded pioneers living on Mars by the end of the century, it’s a dangerous delusion to think we can escape Earth’s problems by mass emigration.

- New technologies in human design could lead to the evolution of new species.

What makes us vulnerable

COVID-19 has been a wake-up call in that it has shown how vulnerable our global civilisation is. It shows how interconnected we are and that it is possible for something to happen which can disrupt life all across the world. No continent is isolated. In Jared Diamond’s famous book Collapse, he talked about how some civilisations collapsed, but none of his examples was completely global. Today, we could have a crisis in one continent, but it would almost inevitably spread around the world. We’re seeing an instance of this in COVID-19. Of course, we can well imagine events far worse than COVID-19 – an event which has the transmissibility of COVID-19 but the fatality rate of Ebola, or something like that. So we can fear something worse that could happen. And we’re much more vulnerable.

Photo by Marcin Osman

Resilience versus efficiency

These threats are very hard to cope with, but we could be better prepared, and we could be more resilient. One of the issues is a trade-off between resilience and efficiency. For example, our manufacturing industry in Europe depends on supply chains coming from the Far East. If some component can’t be produced, if there is one link in one chain that breaks, then that can have a big effect. So one lesson to be learned is that we should have multiple supply chains. We shouldn’t depend on just-in-time delivery.

To give another example, we would have coped better with COVID-19 if all hospitals had kept more spare capacity; if they hadn’t prided themselves – as we in the UK did – on the efficient use of intensive care beds, so there weren’t very many in reserve. In Germany, they intentionally kept at least 20% or 25% of beds free in case there was an emergency. You’ve got to accept that it is worth spending a bit extra in order to be prepared for an emergency, and to manage our industry so it’s more resilient and doesn’t depend on the breakdowns of single long supply chains. Those are lessons we can learn. And obviously, although we can’t completely enforce regulations, we should try to enforce them.

The need to reduce global inequalities

If we think about the world in 2050, it’s going to be very important to ensure that inequalities are reduced: not just the gross inequalities that we have within countries in Europe and the United States, but also the massive inequalities between the North – Europe and North America – and the South, particularly sub-Saharan Africa.

We’ve got to ensure that those gaps are narrower, not wider. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the places that has not yet experienced the so-called demographic transition. The birth rate is still very high. The population is rising there, even though it’s levelling off in Europe and North America. And that’s going to make it harder for Africa to get out of the poverty trap.

Another reason it is going to be harder is that the way in which the East Asian countries developed – the Asian tigers, as they’re sometimes called – was by undercutting the manufacturing costs in Europe and North America and having cheap labour so that we bought their goods. That gave a huge boost to places like South Korea and Vietnam and Taiwan. But now robots are taking over manufacturing, and countries in Africa won’t have that advantage; that ladder is being kicked away.

Photo by Andrea Slatter

The wealthy nations must ensure that countries in Africa can develop industry and develop a better standard of life. What they do have in Africa is mobile phones, so they know what they’re missing. A hundred years ago, they knew nothing about the injustice and the deprivation they face; now they do. So for reasons that aren’t purely altruistic, it’s very important to have a mega-Marshall Plan to develop Africa and ensure it catches up, rather than falling behind the countries of Europe and the United States.

The future of space exploration

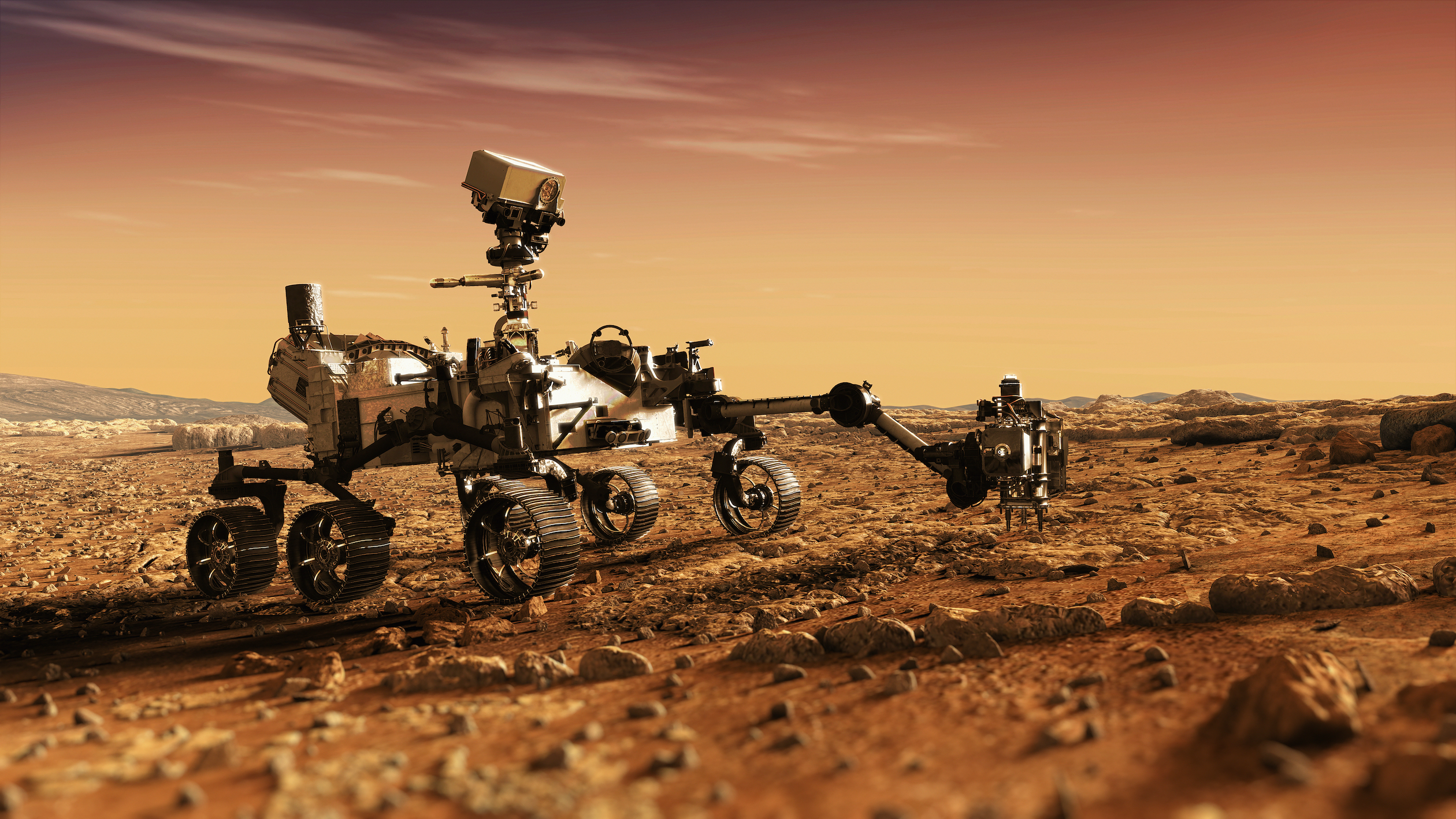

One of my special interests is space science, so I’m a close follower of what’s happening regarding sending humans as well as any instruments into space. Human space flight reached its peak more than 50 years ago when the Apollo programme landed groups of Americans on the moon. That was the high point of manned space flight. Since then, people have been in low Earth orbit, in the International Space Station, but there’s been no revival of space exploration by humans beyond low Earth orbit. Now, it’s an important question: is that going to happen?

I think the motive is going to be reducing because the gap between what humans can do and what robots can do is narrowing. Up till now, humans have been able to do far more in terms of exploring the surface of Mars or fabricating some structure in space than a robot can, but that gap is going to close. When we bear in mind that it’s far cheaper to send robots than to send humans, the practical case for sending humans into space is going to get weaker.

Nonetheless, I do think, and indeed hope, that there will be a revival of space flight by humans. But this will be something which is funded by private enterprise, such as SpaceX, Elon Musk’s company, and Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’s company. These billionaires can fund programmes without costing the taxpayer anything, and moreover, they can fly adventurers who are prepared to take higher risks than any nation can impose on civilians. They can send people into space much more cheaply than NASA or the European Space Agency could; I think they will, and I think we should cheer them on.

Life on Mars?

I think that there will be, by the end of a century, a few people living on Mars, but they will be adventurers accepting high risks, perhaps going with one-way tickets. Elon Musk himself says that he hopes to die on Mars, but not on impact. He’s now 49 years old, so this may happen 40 years from now.

Photo by Evgeniyqw

But I disagree with Musk when he imagines that millions of ordinary people are going to follow and settle on Mars. Terraforming Mars to make its currently hostile environment habitable is far harder than dealing with climate change and the other problems on the Earth. It’s a dangerous delusion to think we can escape Earth’s problems by mass emigration. Space is for robots and adventurers, not for people. Living on Mars is as uncomfortable as living at the top of Everest or on the bottom of the ocean.

Mass emigration doesn’t make sense because the atmosphere of Mars is 1% of the Earth’s. It is not breathable, and the gravity is different. But if we look a bit more futuristically, then those pioneers on Mars will be important in cosmic history, because by the end of a century, we will have the technology to modify the human genome and to design humans that are different from the present ones.

The technology to design humans

This is a technology which I hope will be regulated on Earth for prudential and ethical reasons. But those people on Mars would be away from the regulators, and because they’re ill-adapted to the environment there, they could probably use the technologies we’ll have by the end of the century – genetic modification, perhaps cyborgs, interfaces with machines or electronic computers – to adapt themselves.

Within a few hundred years, they would become a new species. And if they become a new species, with a far longer lifespan, then they could adapt to Mars and they could voyage further away, maybe into the blue yonder, beyond our solar system.

We’ve got to bear in mind that intelligent life has a vast future. The Earth has been around for 4.5 billion years, but it’s less than halfway through its life. It’s got to go another 6 billion years. During that time, the amount of evolution that can happen may be as dramatic as that of the first protozoa to humans over the last 4 billion years. We just can’t conceive what type of intelligence may exist billions of years from now – not just here on the Earth, but far beyond.

Discover more about

the survival of global civilisation

Lightman, A. and Rees, M. (2025). The Shape of Wonder: How Scientists Think, Work, and Live. Pantheon.

Rees, M. (2022). Is Science to Save Us?. Polity.

Rees, M. (2018). On the Future: Prospects for Humanity. Princeton University Press.

Rees, M. (2012). From Here to Infinity: A Vision for the Future of Science. W. W. Norton & Company.

Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (2025). Report. University of Cambridge.