One of the dangers of machine learning is that the algorithm you would produce is only as good as the data on which it relies. To take a crass example, but an important one nonetheless, if you have a machine that tells you whether a mole on somebody’s body is worrying in terms of potential malignancy, and that machine has been trained only on light-coloured skins, then it might not be as good at detecting malignancy when it looks at moles on dark-coloured skins. People are really worried about racial bias, for example, in algorithms. If the data is skewed or biased, what you get out of it will also be skewed or biased.

AI, ethics and medicine

Professor of Law

- Machine learning and artificial intelligence have the potential to transform medicine. However, algorithms are only as good as the data sets on which they rely – biased data will lead to biased results.

- The way the law deals with emerging technologies like genome editing is to allow its use for research purposes while requiring much more evidence before this can be used in patients.

- Public education and consultation are key to developing the regulation of new technologies and enabling science to progress.

Transforming medicine

Machine learning and artificial intelligence have the potential to transform medicine in an incredibly wide range of ways. For example, doctors learn how to interpret the scans that they look at by looking at lots of them. Machines can do that with an infinite number of scans and learn much more quickly and accurately to diagnose what they’re seeing. So, one potential consequence is replacing humans with machines to do things like read and interpret scan results.

Photo by Zapp2Photo.

The value of data

Huge data sets have the potential to enable us to do medical research much more quickly and thoroughly, because obviously the more data you’re learning from, the better. The NHS is now aware that its data of the medical treatment of everybody in the UK isn’t just an important source of information for doctors, but it is actually valuable. This idea of data sets as having value is a relatively new development in medicine.

Something that lots of people are not necessarily aware of is that the smartphones that they carry around with them in their pockets are gathering health data about them and are sources of health data. We normally think of health data as being something that’s kept in locked filing cabinets and treated as confidential, but our mobile phones contain an enormous amount of information about our fitness and health.

From the way in which you use your keyboard, big data companies can identify the early signs of Parkinson’s disease. By engaging with big data companies, you are telling them an enormous amount of information about yourself. Tracking flu epidemics, for example, can be done very easily by tracking search terms in Google; people searching for symptoms means that it’s possible for Google to tell more easily than other public health agencies where a particular flu episode is increasing. What we’re seeing is a recognition that the preoccupation of big tech companies with data also has huge health implications as well.

How the law deals with emerging technologies

Genome editing is an especially exciting new development. The inventors of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system, which is essentially a much simpler way to edit a genome than was previously thought possible, won the Nobel Prize. The way the law approaches something like this is to say that this might be very exciting for research purposes, but we must not do it in the clinic until we know about its long-term safety.

Worldwide, there’s a consensus among scientists that while it’s incredibly exciting to carry out research involving genome editing, perhaps even on human embryos, it should never be used in treatment. That is why the Chinese doctor who announced that he had edited the genomes of babies that have been born has gone to jail; it was regarded as beyond the pale, scientifically. So, the law says you can do this for research purposes and we need to learn about this, but we need a whole lot more evidence before you can actually do this using patients.

When preimplantation genetic diagnosis is permitted

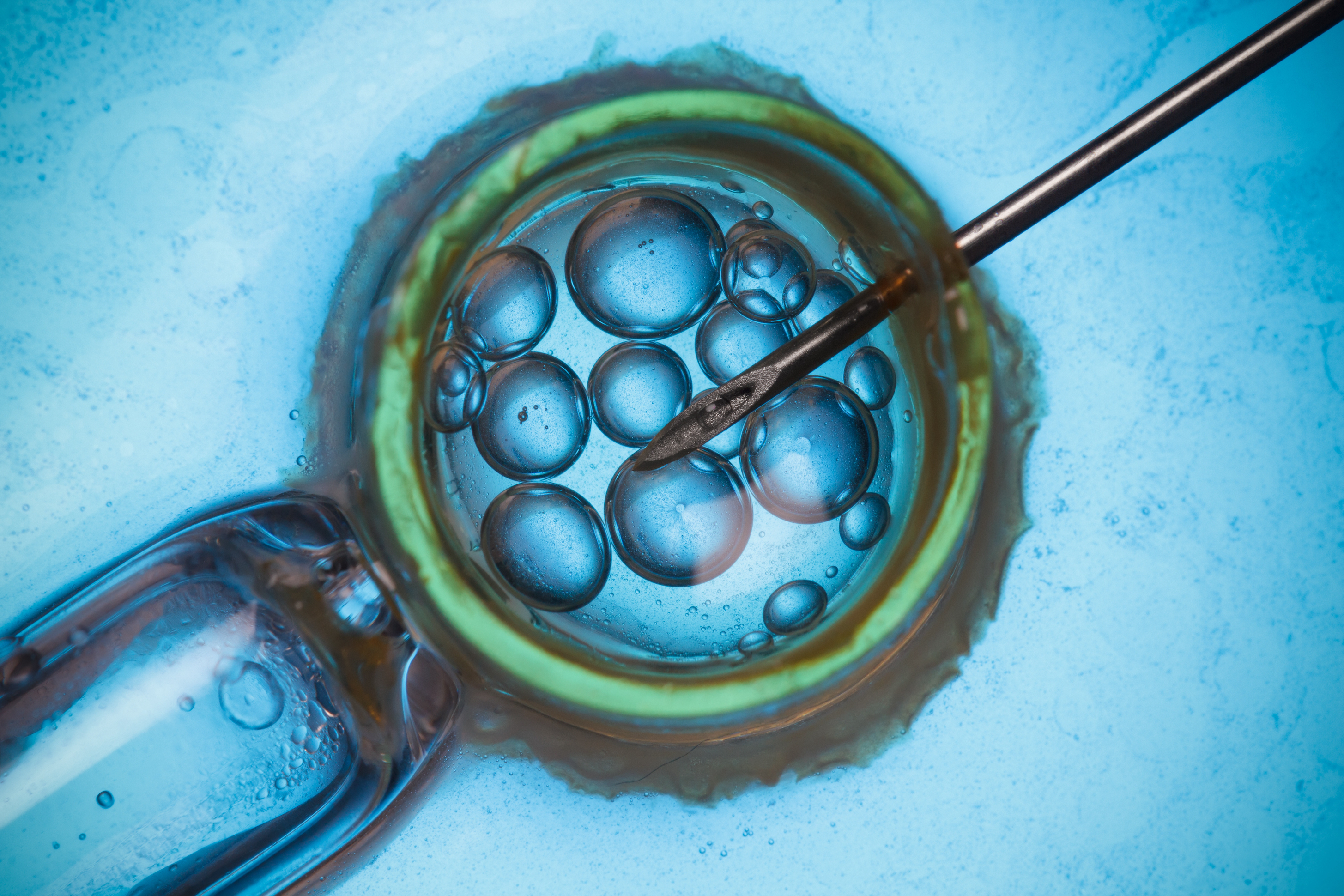

It’s not currently possible to edit a baby’s genome before in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment. That’s absolutely illegal, and a change in the law would be necessary before that became possible. But it is possible – and has been since 1989 – for couples to undergo something called preimplantation genetic diagnosis. That would be where you go through the first part of a regular IVF cycle, you create embryos in vitro and those embryos are tested to see if they suffer from a genetic condition that runs in your family. That enables you to transfer to the woman’s womb only those embryos that are unaffected by that genetic condition.

Photo by isak55.

This has been possible for a very long time, and there are rules about the circumstances in which you can undergo preimplantation genetic testing. There needs to be a significant risk of a serious disability. If people wanted to do preimplantation genetic diagnosis to choose a girl, that would not be within the law. But if you had a very serious condition in your family, such as cystic fibrosis, you could select to ensure that your baby didn’t inherit that condition. So, this is a way for people to go through pregnancy knowing that the baby that they give birth to will not have inherited the condition that perhaps a first child has had, or that they know runs in their family.

In the UK, it’s also lawful to undergo preimplantation genetic diagnosis in order to choose an embryo that will be a good tissue match for an older sibling. Again, the condition has to be a serious one, and it has to be likely that it can be cured or treated effectively with cells taken from, for example, the umbilical cord or a bone marrow transplant. So, the law enables people to decide to have a baby in order to be a good tissue match for an older sibling. Of course, people with a sick child who could perhaps be treated with umbilical cord stem cells could just have another child naturally. So, people can do this without artificial assistance; it’s just their chance of success in that case will be lower.

Consulting the public to develop regulation

Something that has been incredibly important in recent years in the regulation of new technologies is the importance of public consultation and public education campaigns. Rather than just having an expert regulator which makes the rules and decides what’s going to happen, there’s an increasingly important emphasis on making sure that the public have been consulted. That consultation isn’t just a survey but involves providing accessible information to the public to help them understand what’s being proposed, the issues, and the advantages and disadvantages.

Regulators increasingly recognise that public buy-in is really important. If the public is content that the regulator has a firm hand on what’s going on, it will allow science to progress without facing campaigns against this progress. There’s a lot of mutually beneficial elements to public consultation; it’s really helpful if the public are on board with any changes.

Public education campaigns

Some years ago, the UK changed its law to allow something called mitochondrial replacement therapy. This is where a woman has a genetic problem in her mitochondrial DNA – this is the outside shell of the egg, which doesn’t contain that many genes – and it can cause very serious disease. The question was, should it be possible to use the outer egg of a donor and the nucleus of the woman suffering from this condition in order to create an embryo?

Of course, you can imagine the “three-parent IVF” tabloid headlines for this, because you’re using the eggs of two women to create an embryo. But the UK’s regulator engaged in an intensive public education consultation to better inform people about what these diseases are and what the process involves. Obviously, not everybody would have seen that and not everybody would have felt properly consulted. Nonetheless, it was a good example of a difficult, complicated technical process that was explained very simply through cartoons and other accessible materials that were put into the public domain to tell people what was going on. While lots of the public wouldn’t have seen that consultation, it was still a really important effort to try to explain something to the wider public.

When are new technologies safe enough?

Photo by nevodka.

When we’re thinking about new technologies, there’s this really difficult question about when you first use them in human beings. This question arises in relation to drug trials; it arises in relation to new reproductive technologies. This is a difficult question, because the question really is, when is it safe enough? You’re unlikely ever to have proof of conclusive long-term safety, in the sense that somebody has to go first. That’s the case with a new medicine; it’s the case with a new reproductive technique.

What’s important is that we have robust regulatory bodies in relation to medicines, vaccines and reproductive techniques that are studying the evidence and making a considered judgement about when something becomes safe enough to try in human beings, while also continuing to gather data.

It’s worth remembering that with some techniques, somebody had to be the first person to do it, when you couldn’t have known whether it was safe. In relation to something like in vitro fertilisation, a lot of people owe a huge debt of gratitude to the women who went first when it had never safely been done in human beings before. That must have been extraordinarily stressful. Obviously, the results have been happy ones, in the sense that IVF has been a very great force for good, certainly in my view. Yet, that judgement call about when something is safe enough to try in humans is tough, because if you always require absolute proof of safety and adopt a precautionary principle, there will be things you’ll never do.

Discover more about

the ethical and legal implications of technological changes in medicine

Jackson, E. (2019). Medical Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Jackson, E. (2012). Law and the Regulation of Medicines. Hart Publishing.

Flessas, T., & Jackson, E. (2019). Too Expensive to Treat? Non-Treatment Decisions at the Margins of Viability Medical Law Review, 27(3), 461–481.