This is recovered through the restoration of the antique in the Renaissance and made into a systematic procedure, through the recovery of the so-called geometric rules of optical perspective, from Brunelleschi to Alberti, to somebody like Vasari. That becomes a matrix into which everything is poured. That, in turn, becomes a procedure for thinking in general, with the Cartesian Cogito, ergo sum; that is, the thinker is privileged over the context. To cut a very long story very short, it’s with Romanticism that one begins to see an appeal to the deeper context.

Understanding our cities to understand ourselves

Emeritus Professor of Architecture

- We’ve inherited a tradition in architecture in which the visual is prioritised, which can be a problem.

- It’s with romanticism that one begins to see an appeal to the deeper context.

- I would get rid of the term “perception of”, which we use to describe involvement with architecture, and say “involvements with”.

The priority of the visual

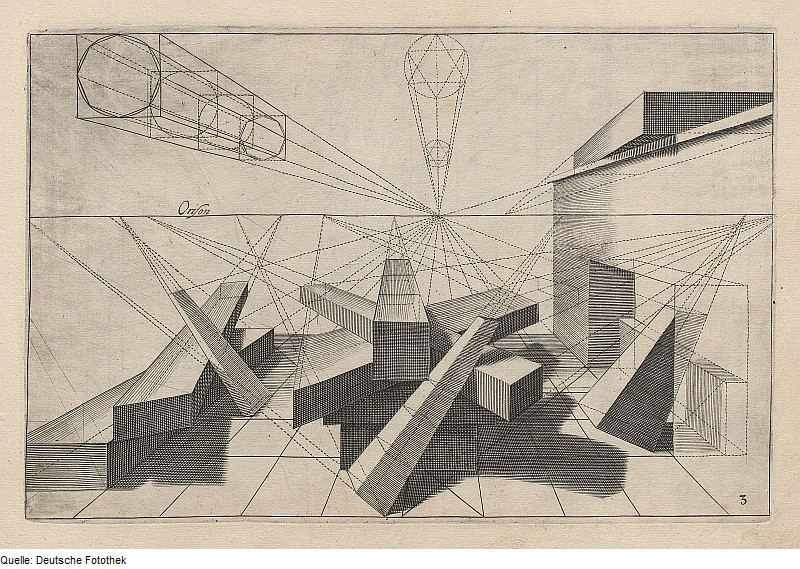

We’ve certainly inherited a tradition in both schools and in the profession whereby all the activity surrounding architecture – its construction, its inhabitation – is measured against what it looks like. This is inherited from perspective practice and is probably fortified by the degree to which what first happened in the ateliers. This idea that there is a reality given over to a viewer that can be coordinated by plan section and elevation in terms of drawings means that the priority of the visual is forced to carry all the other modalities of a city, its civic life and the metabolism by which it thrives.

Architektur & Geometrie & Perspektive by Hans Vredeman de Vries

Problems with prioritising the visual

One of the problems of this notion of architecture as presented to our view, is that, unlike what one finds in Joyce’s Ulysses, we actually consume the architecture mostly in peripheral vision, and even then it doesn’t come alive as a view, but as a topic, with emotions and values attached to it as part of something else, a situation. Recognising that, one starts tracing the deep background of what these situations are like, and one recognises, for example, that there’s a structure of dependency.

One’s thoughts move very quickly; what one says moves slowly. That, in turn, is supported by gesture, which in turn is supported by the furniture, which in turn is supported by the walls and floor, which move slowest of all. You need all of that in place. You don’t just get, as it were, thoughts in the void.

Perspectivity

One first sees perspectivity in Hellenistic Alexandria, which is recovered and systematised in the Renaissance. It’s probably the case that the combination of theatre with Euclid puts it together in a way that makes it germane beyond strictly the theatre. That is to say, theatre itself becomes a way of understanding how “proper people” behave.

The Story of Lucretia, c. 1500. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts.

An appeal to the deeper context

For example, we can view Schelling’s Naturphilosophie as an attempt to see the world as what Heidegger would call ‘worlding’, as developing out of its own resources, of which humans are a part, rather than the agency, the privileged understanding. This will be made explicit in Heidegger’s "worldhood of the world" and in Merleau-Ponty’s notion of embodiment, by which he sees that the world that we inhabit is embodied in the things with which we’re involved. So, I would get rid of the term “perception of”, which we characteristically use to describe our mode of involvement with architecture, and I would say “involvements with”, since the way we are with one another, with things, with nature, is much more indirect – it’s distributed, it has a depth structure and it is something of which we’re a part.

The public and the private

People have developed a procedure for mapping the city as public-private. Giambattista Nolli drew a map of Rome, where buildings were black and what was “public” was white. I would argue that there is almost nothing in a city that is purely private – maybe the domestic lieu, and that depends on whether you take your showers by yourself; otherwise, everything else is qualified by involvement with others in one form or another, either directly or implicitly.

Taking something like the Japanese tea ceremony, one can see a structure that’s highly ceremonial. One doesn’t simply pick the tea up and slurp it: drinking is almost secondary to the rest of the performance. Now, when you’re drinking your plastic cup of builder’s tea, you don’t have that degree of ceremony, but you have bits of it. One is always caught up in these structures that are more or less free, more or less affordances.

Topographic depth

I refer to topography as a resistance to using words like space. Topography speaks of a bottom-up way of understanding how things are distributed spatially and under what circumstances. They don’t occur in a void or floating, except possibly in a collage. In fact, there are structures of dependency, as we saw earlier with the movement from thoughts to speech to gesture to furniture to walls and floor of a room. One’s intelligence is not simply a Cartesian theatre – it is already embodied and distributed in the given context. It doesn’t have to be neat. A mess is a form of order. Violence is a form of order.

In contrast to the overconfidence to be able to command reality as a concept that space promotes, I am arguing for taking proper account of the embodied, metaphoric and distributed context. Moreover, all of this distributed context is temporal. A thought, a fly, a brick wall each have different temporalities, and so to speak of space or time in the singular is to do an injustice to understanding the order in which we’re involved. One can trace this idea from individual situations whose dependence on their contexts is obvious, particularly at an urban level.

Dependency on context

Tallinn Town Hall in Town Hall Square or Raekoja Platz. This impressive old building has a history of over 600 years. Photo by Jono Photography.

For example, a block can last for 500 to 600 years, whereas the buildings that make it may be changed every 100 years. The buildings on the street have a narrower range of decorum than the interior of the block, which is much wider: workshops, gardens, high-rise buildings. Similarly, even at an architectural level, a window or a door is more volatile temporarily than the wall which supports them. The part of the desk at which one is working is more volatile temporarily than the rest of the desk, where the books are stacked. The desk itself moves slowest of all, always anticipating what might happen because it “remembers what usually happens there” and recognises the modes of connectedness of this deeper order. This enables us to move from local to more general to regional contexts, while keeping track of the rich life of a city that both challenges the inheritance of space and form, and acknowledges the claim of urban life and of the city.

Welcome to the deep Matrix

If I had to summarise it, I would say that it’s important to understand that the city is distributed, embodied, enacted, metaphoric and temporal, and it is a deep matrix or metabolism which exerts a claim upon our understanding and an opportunity for our self-understanding, to make cities that are habitable, creative and fruitful.

Discover more about

how we view architecture

Carl, P. (2015). Convivimus Ergo Sumus. In H. Steiner & M. Sternberg (Eds.), Phenomenologies of the City: Studies in the History and Philosophy of Architecture. Routledge.

Carl, P. (2001). The Grid and the Block. Architectural Research Quarterly, 5(2), 101–103.

Carl, P. (2000). Urban Density and Block Metabolism. In K. Steemers & S. Yannas (Eds.), Architecture, City, Environment: Proceedings of Plea 2000 (pp. 343–347). James & James Ltd.