Consciousness is usually defined as the subjective feeling of what it is like to have an experience. That is somewhat circular, but we can define consciousness with reference to its absence. There are many mental processes that we think of as being entirely unconscious. I am not conscious of the brain processes that are enabling me to see things in three dimensions. I am not conscious of the processes that contract certain muscles as I move my hands. There is a subset of our mental lives that we are conscious of, and we can communicate that to others. We can experience it in a way that allows us to remember it, to do things with it, to manipulate it and then ultimately tell each other about it.

Conscious and unconscious states

Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience

- Consciousness is the limited subset of mental activity we can subjectively access and report, while most perceptual and motor processes unfold unconsciously.

- According to reality-monitoring theory, conscious experience tracks neural states that faithfully represent the external world, marking them as more reliable than purely internally generated activity.

- Hallucinations in conditions like schizophrenia likely arise when internally generated signals dominate perception and reality-monitoring mechanisms fail to flag them as imagined.

- Functional-MRI studies reveal that a small proportion of patients diagnosed as vegetative can voluntarily engage imagery networks, showing covert consciousness despite the absence of outward responses.

What is consciousness?

© Pexels

© Pexels

Theorizing about consciousness

There are different ways of theorizing about consciousness. Some theories are aspiring to be universal theories that attempt to say something about consciousness in any physical system, and this is a radically distinct metaphysical picture from one that assumes consciousness is tied up with the psychological properties of how the human mind, and perhaps other animal minds, work.

The word consciousness is often used in a variety of different ways. One useful distinction to make in this field is between the notion of global states of consciousness; when you vary from being in a deep sleep to being anesthetized to being fully awake, you are changing in your global state of consciousness. Even when you are fully awake and alert, there might be some brain processes, some mental processes, that you are unconscious of and others that you are conscious of. Consciousness scientists are interested in both of those notions of the word consciousness, but unfortunately, we have this single word that applies to both. It is really important to keep them conceptually distinct.

Conscious vs unconscious

There are many competing perspectives in the field that attempt to explain the difference between conscious and unconscious states in the brain. One perspective that we are pursuing in our lab is rooted in theories of reality monitoring.

© Pexels

© Pexels

Reality monitoring is the capacity of the brain to distinguish between activity that is internally generated — for instance, activity generated by expectations, working memory or imagination — and activity generated by a feature of the outside world. We think one explanation for conscious experience is that consciousness is tracking those brain states that are reliable reflections of the outside world, and it is discarding the ones that are simply internally simulated, generated or due to internal noise. One hypothesis about the functions of conscious experience is that consciousness is tagging certain neural representations as being reliable reflections of the outside world, and this is why consciousness has what philosophers call assertoric force. It forces us to believe in the reality of the outside world — that is its job.

Comparing to Freud

Freud was right that there is a wide range of unconscious mental processes, but these are less exciting than Freud liked to imagine. These are things like processes involved in organizing particular sequences of muscle contractions or processes involved in how we build up a visual representation of the outside world. All of those are unconscious aspects of how our brains are working, and certain parts of our mental life then become conscious and reportable to others. That endorses a distinction between conscious and unconscious processes, but it jettisons the just-so stories that Freud liked to tell about the reasons for some of the unconscious drivers of behavior.

Reality or imagination

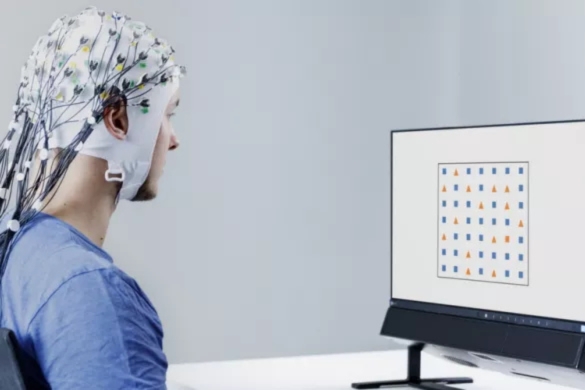

One line of work we have been pursuing on consciousness has been examining how people are able to distinguish between reality and imagination, or aspects of their mental life that are internally generated. The way these experiments work is that we ask people to imagine a simple stimulus on a computer screen, such as a set of tilted lines, and we ask them to imagine this embedded in flickering noise on the screen.

© Tobii AB

The trick we have in the lab is that on some trials we gradually fade in a real stimulus. That stimulus can either be the same as the one they are trying to imagine, or it can be something different. We find that people readily experience confusions between reality and imagination in this setup. When we ask people to judge whether a stimulus has really been presented, if they happen to be vividly imagining that same stimulus on a particular trial, then they are more likely to say something real was out there. It is as if the signals from imagination and perception are becoming intermixed in the mind. Using functional MRI, we find that this intermixing is taking place in mid-level visual cortex, towards the back of the brain, in an area known as the fusiform gyrus. We then see other regions of the brain in the insula and the medial prefrontal cortex, towards the front of the brain, tracking how strong those signals are, how reliable they are, and using that information to judge whether something is real or imagined. We think that these areas of the brain working together can accomplish reality monitoring.

The visual cortex

This work is consistent with the proposal that when we imagine something, we use the same resources within the brain as when we actually perceive that same thing. If I perceive a dog sitting on the rug in front of me and then close my eyes and try to imagine that same dog sitting on the rug, I will activate similar neural populations in my visual cortex to those activated when I actually perceive the scene.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

The brain then faces a difficult problem: it needs to figure out whether activation of those neural populations in the visual cortex is being caused by the real world out there or is somehow internally generated. We think that the operation the brain is trying to engage in is key to understanding distortions in how people confuse imagination for reality, for instance in cases like hallucinations.

Origins of hallucinations

One powerful perspective on the origins of hallucinations in conditions like schizophrenia is that they reflect an imbalance between how much of our perception is internally generated and how much is driven by the outside world.

© Pexels

© Pexels

If we turn up the dial on these internal processes, we might start activating perceptual areas of the brain in a way that is completely divorced from reality. If, in those situations, we also have distortions in reality monitoring — if people are unable to realize that those internal processes are in their imaginations — then they might think that they are as real as the outside world. This perspective can explain why someone may not only experience hallucinations but also lack insight into the fact that those experiences are hallucinatory. A distortion in metacognition or reality monitoring can lead people to not have the self-awareness that their perceptual experiences might not actually reflect the outside world.

Disorders of consciousness

There are a variety of disorders of consciousness where people might, due to brain damage or other injury, enter a coma or a vegetative state. These can be cases where the sleep-wake cycle remains intact; physiologically, people seem to wake up and go to sleep again, and yet there are no signs of any internal conscious brain processes. A subset of those cases does show some signs of conscious experience, and this has been an amazing discovery by colleagues of mine, particularly Adrian Owen in Canada. He has shown that it is possible, in a small number of patients who are in a vegetative state, to communicate with them by asking them to imagine particular experiences.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

These patients are unable to speak or produce any behavioral response, but if they are placed inside a functional MRI scanner and asked to imagine doing things like playing tennis or walking around the house, some — a small subset — can voluntarily activate circuits in their brains that are normally activated when a healthy person imagines similar experiences. This suggests a residual capacity for imagination, and therefore for conscious experience, in patients who are otherwise entirely behaviorally unresponsive. It shows that, in a small number of cases, obviously with huge clinical importance, there are patients in these states of unresponsiveness who are nevertheless still conscious at some level.

Consciousness and metacognition

Metacognition and consciousness are related, but I do not think they are the same thing. Metacognition appears to be what we call consciousness-selective. When we are conscious of some stimulus or some information, we are then also able to engage in metacognition about that information. I can reflect on whether the stimulus I have just seen was an A or a B. I can reflect on whether I have made a good decision about where to go on holiday, and all that information is consciously represented. There are many lines of empirical evidence for this. For instance, in cases of blindsight, patients who have had damage to the back of the brain — the visual system — may still be able to carry out certain tasks even though they feel that that area of space is entirely blind. They feel as though they are blind, and yet they still seem able to process some visual information. One way of thinking about this is that what is happening is some aspects of their behavior can be driven unconsciously, but they have no metacognition about those processes. They cannot introspect about how they are achieving this high level of task performance. That shows us there is a tight coupling between being conscious of something and having good metacognition about it. This then leads to the hypothesis that perhaps one reason for this tight coupling between metacognition and consciousness is that some of the same computational processes that are important for consciousness are also important for metacognition and vice versa. One of those processes may be monitoring the reliability of our brain representations of the outside world. This provides a deep conceptual link between work on metacognition and work on consciousness.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

states of the brain

Fleming, S. M. (2021). Know thyself: The science of self-awareness. John Murray Press.

Fleming, S. M., & Dolan, R. J. (2012). The neural basis of metacognitive ability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1594), 1338–1349.

Fleming, S. M., & Lau, H. C. (2014). How to measure metacognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, Article 443.

Fleming, S. M. (2020). Awareness as inference in a higher-order state space. Neuroscience of Consciousness, 2020(1), niz020.

Dennett, D. (1993). Consciousness Explained. Penguin.