The power of crowds

Many political thinkers during the 19th century are concerned with how to integrate the masses into politics. This is true during the political revolution and the Industrial Revolution. In fact, this issue is key to events throughout the 18th and 19th century such as the French Revolution.

Throughout this period, people are amassing in cities rather than the countryside. Droves of people are migrating into overcrowded conditions. A vast literature develops, addressing crowds and power. Overall, 19th century debates about magnetism and hypnosis are very much concerned with group processes, not just individual suggestibility.

Crowd psychology draws on ideas about psychiatry, the mind, madness, deviance and pathology. It eschews individual criminality or perversion; instead focusing on the capacity of groups to behave rationally and adopt civilised codes of behaviour. Conversely, it also examines the terrifying potential of a violent mob to threaten stability as well as the propensity of groups under certain kinds of influence to lash out.

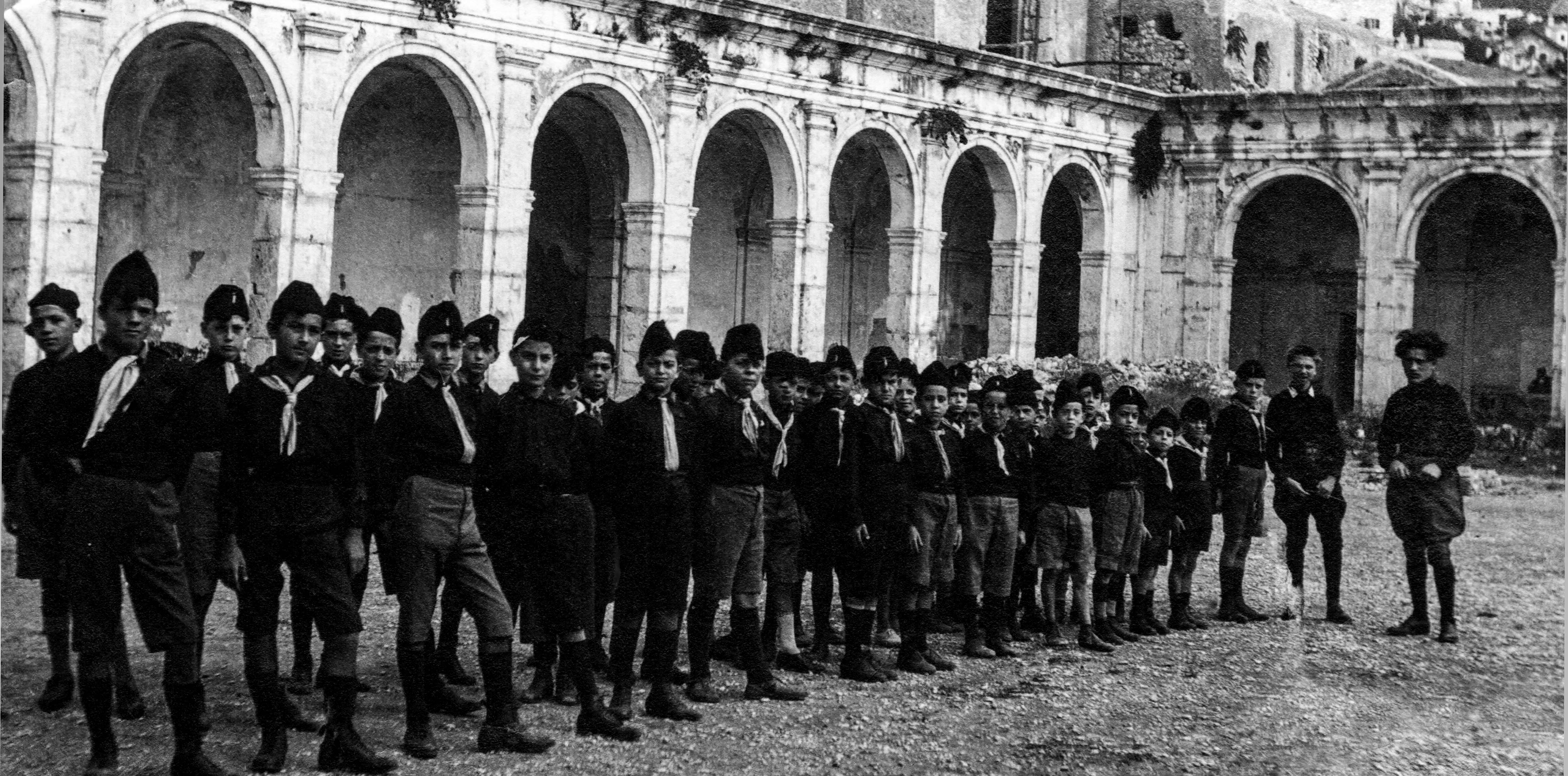

This literature on the crowd emerges in the 1880s and 1890s. It is often written with a tremendous sense of anxiety and apprehension about what the public can do. Several studies on crowds are produced during this period in Europe and America. A lot of this literature addresses so-called “elites”. There’s another branch of theory called elite theory, which speaks to the role of political elites during the age of mass civilisation. Indeed, it looks to orchestrate and govern a potentially monstrous crowd force.

Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego

In 1921, Freud writes his landmark text on crowd psychology, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. Although the piece is often neglected, it is insightful in several ways.

In Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, Freud reflects on crowds as well as earlier literature on the topic. He refers to work done by Gustave Le Bon and considers where he agrees and differs with theory. However, Freud also incorporates ideas about social networks and other group structures important to people. Yet, his main argument develops from the idea that psychic life itself is relational. In other words, in our minds, we’re always relating to others.

Moreover, Freud offers thoughts on the division between the branches of individual psychology and social psychology. He feels this division is arbitrary because he believes individual psychology is social psychology; that is, from infancy, people develop as individuals by mentally relating to others.

Freud is setting the scene with this text. He’s writing it right on the eve of the emergence of fascism in the aftermath of the First World War. Freud is also thinking about the group processes that led to the militarism and nationalism of the period. He even admits he was temporarily caught up in the fervour. In 1914, he says that, at one point, all of his libido was given to Austria; that is to say, he had invested a kind of love and desire in the nation that one would usually reserve for a mate. However, he later steps back and reconsiders the destructiveness of war with horror. Indeed, these observations shape Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego.

Yet, one could also read the text as a reflection on the psychoanalytic movement itself. After all, the movement is an institution and thereby another group process. Freud begins musing about the unconscious dynamics that operate in his group of psychoanalysts while considering his role as a leader. He reflects on all the schisms, tensions, rivalries and complexities of human relationships in the group.

Regardless, his work is developed by others in myriad ways during the interwar period. Of course, it’s meaningful to remember that this work on group psychology occurs in the shadow of Nazism and Stalinism.

Wilfred Bion

By the Second World War, the study of group psychology has developed in another vital way; namely, the use of the talking cure in group therapy. This represents an attempt to explore group phenomena in practice as opposed to theorising from above. Such investigation involves bringing entire groups into the consulting room for therapeutic help.

An army doctor, Wilfred Bion, is a pioneer of this development. He is a significant theorist in psychoanalytic thought, who initially builds upon Freud’s work and the ideas of Melanie Klein and others.

Over time, Bion develops as an original theorist in the space. He works with others, including his ex-analyst John Rickman, during the Second World War to help soldiers. These soldiers have broken down and come to his psychiatric hospital in England.

Around that time, clinicians in the US Army are thinking about how to help combatants suffering mental health difficulties such as shell-shock. These difficulties involve incapacitating symptoms that have no clear organic explanation.

During the First World War, a wide range of techniques and practices, including talk therapy, are applied to these patients. However, by the Second World War, group therapy is being developed in its own right. Rickman and Bion are instrumental in this, though pioneers such as Norbert Elias and S. H. Foulkes advance the practice.

Developing group therapy

Throughout his work with soldiers, Bion participates in the group. Although he is the organiser, he eschews the role of leader. Instead of directing groups in a hierarchical manner, he allows them to develop as they see fit. Bion is present throughout sessions, but he simply observes what emerges and interjects very little.

Naturally, one issue that emerges is anxiety over the lack of direction in the sessions; after all, Bion is not saying what should or shouldn’t happen. Nevertheless, members of the group start to take responsibility and assume some leadership.

Bion advances this notion of a potentially leaderless group therapy session. The session is free to develop one way or another, and Bion interprets what occurs. This becomes a significant development in thinking psychoanalytically in group situations. Bion writes papers on the topic, which culminates in his ground-breaking book published in 1961. As such, he helps make this branch of psychoanalysis impactful in its own right.