Spinoza is very interested in this question of the relationship between the body and the mind, and he approaches it at several levels. To understand the significance or the interest, perhaps, of his view, it’s useful to consider who his opponents are. He rejects the materialism of his contemporary Thomas Hobbes, who says that our thoughts are just motions – material things. Spinoza never doubts that bodily motions and thoughts are ontologically of quite different types and that one cannot be reduced to the other.

The other giant figure who looms in the landscape and who Spinoza opposes is Descartes, who famously thinks of the human being as a composite made up of two substances: a body and a mind. Spinoza rejects the idea that it’s enough to think of one’s body and one’s mind as these two separate entities which are somehow stuck together.

Spinoza’s philosophy on the body–mind connection

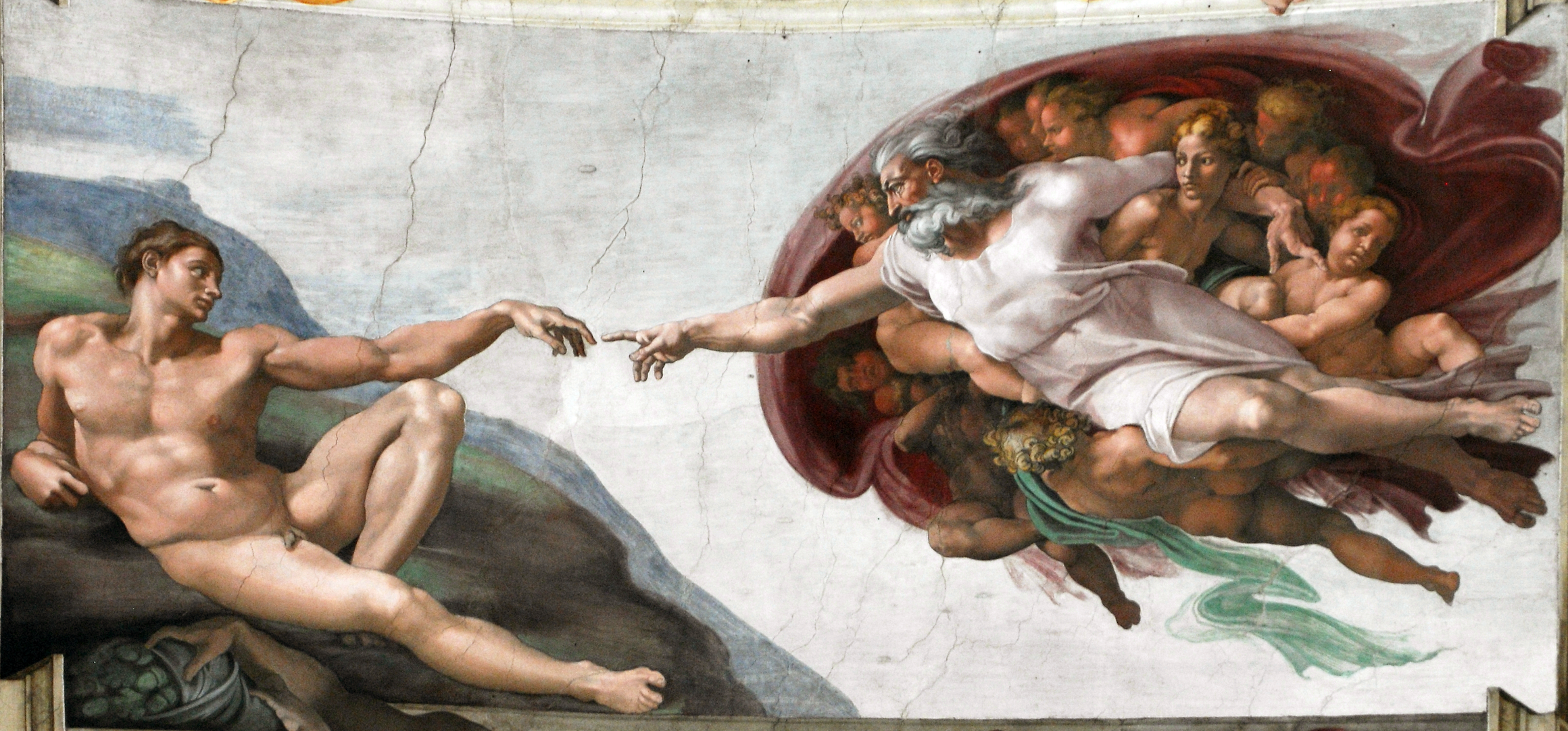

Spinoza’s project is to stick body and mind more closely together without reducing one to the other. Maybe the best way to start understanding this is to think about his view of the mind of a single human being – you or me. Spinoza says that the first idea that constitutes your mind is an idea of your body. So, we can see that the body is there from the start and the existence of the mind depends on the existence of the body. Now, we might want to know what is this idea of the body which constitutes the mind. Spinoza’s quite specific here. He says it’s an idea of the way our body is affected by some external body.

The affect of an external body

First of all, it’s about the way you are sensorially affected by some other body: by a taste, smell or feel for example. At the same time, it’s an affective idea. Spinoza thinks of these ideas not just as neutral experiences but as experiences that are already alarming or pleasant. You might find the touch of a cold hand on your back repulsive, or you might find a loud noise frightening. Packed into the idea of the affectiveness of these ideas is a further element, which has to do with the presence of a designer. We’re already understanding the cold hand as something that is undesirable, that we want to get away from. We might already be understanding the taste of comforting milk as something that’s desirable, that we want more of. So, there are complexities from the very beginning, They’re always there in the mind and they are manifestations of what the mind is. Spinoza is emphatic that these are ideas of the way our body is affected by other bodies. So, the other bodies, the external world, are there from the start. We never have to cope with this isolated ego, which people sometimes find to be a problem with Cartesianism.

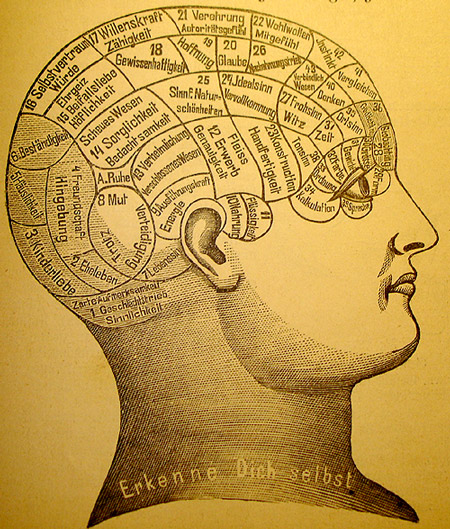

The ideas that constitute the mind in this way are, Spinoza says, very confused. They tell us more about our own body than they do about the external things that we’re being affected by. So, first of all, they are a manifestation of our capacity to experience our own body, but they also tell us more about the way our body can be affected – what it’s like, for example, to feel something cold and repellent or to taste something warm and comforting – than they do about the external thing. If all I know about this hand on my back is that it’s cold and repellent, then I’m free to imagine it in all sorts of fantastical ways. I don’t have much of an idea of what the hand is, but I do know something about my own body, which is how it’s responding.

What Idea do we Get of our Bodies?

The idea that we get of the body is also extremely confused. If you think about building up an idea of your body from the way it’s affected, then certain parts of the body may figure more largely than others; certain capacities of the body may be more prominent than others. So, we have these patchy and incomplete ideas. Spinoza is not particularly bothered by that. He thinks that the ideas we start with are confused.

There is a more worrying feature of this account, which is that the mind is presented as a passive kind of register of the things that are going on in the body. This is not at all what Spinoza wants us to understand.

What is Spinoza’s philosophy of the embodied mind?

Spinoza believes that thinking is a dynamic, active process which has its own power and impetus. So, the question is, how is he going to get that into the picture? Here, Spinoza turns to a big metaphysical claim, which is rooted in the thought that an embodied mind of the kind he’s describing exists for a certain period of time. He thinks that to go on existing for this period of time, the embodied mind has to be exercising a certain power to go on existing. As a body, it must, for example, be resisting the pressure of the other bodies that are around it so that it survives as the body that it is. As a mind, it has to be exercising the power to go on, processing its own ideas. Spinoza calls this power the “conatus” of the individual, and he describes it as a striving to persevere in its being. He thinks the embodied mind does this with all the powers it has.

The body strives to persevere in its being in accordance with the laws of physics. It is itself a complex body with many internal motions and it is trying to hold itself together in the face of the environment. The mind also strives to persevere in its being. It strives to go on thinking in more powerful ways in accordance with what Spinoza describes as psychological laws. For example, the mind associates one idea with another. It forms expectations in light of the ideas it’s had so that it builds up a more complex mental life and a more complex understanding of its own body.

Now, obviously, not all these ideas are directly ideas of its body. Suppose you were thinking about the differences between animal species. You wouldn’t directly be thinking about the way your body was being affected. So, it looks as though, as far as thinking goes, parts of thinking no longer come to be ideas of your body. But I don’t think that’s what Spinoza means. I think that, on the contrary, what’s happening is that your idea of your body is just becoming a more complex idea of your body; not as an isolated thing, but as a body situated in a very large and increasingly complex natural environment in which it interacts with things in different ways. All your thinking is built on top of that assumption.