About one third of women report experiencing physical violence, sexual violence or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. That’s data from the US, but the numbers worldwide are not better; in some countries, they’re much worse. What we’re dealing with is something that is very, very common. Because of this, in the US, most major medical organisations recommend routine inquiry of women by their healthcare providers for intimate partner violence, particularly for women of reproductive age.

Individual practitioners are therefore encouraged to ask, and there are evidence-based approaches to asking that have been shown to be more effective. Behaviourally specific inquiry is the best approach. That means avoiding vague questions, like ‘Are you being abused?’ and instead asking, ‘Does your partner hit, kick or choke you? Does your partner force you to do something sexually that you don’t want to do?’ Those types of questions have been shown to be more effective.

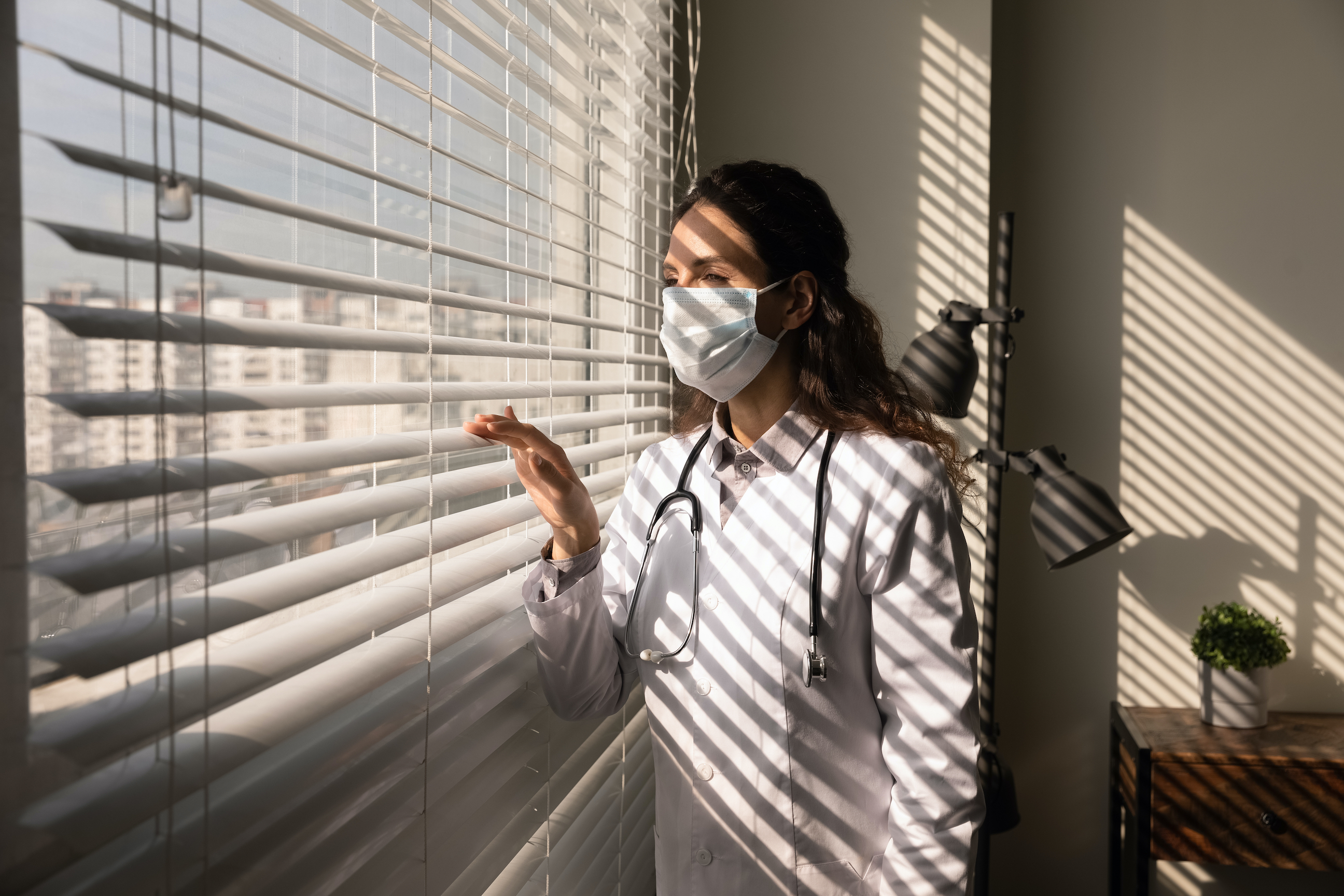

It's vital to ask these questions privately, with no one else in the room. Privacy is incredibly important. First, you would never want to ask a woman who is potentially being abused about the violence in her life if there was someone else in the room who could potentially be the abuser or tell the abuser. Second, you’re probably not going to get a positive answer where one exists if you’re not asking in a private, safe space. Another thing to keep in mind, and there’s been qualitative literature on this, is that women in general – not just women experiencing abuse – do not mind being asked. So asking directly in a private setting is not only okay, but it’s recommended.