So, there's a debate that develops. It's a debate amongst intellectuals. That is to say, how can you justify in terms of scripture, in terms of Christian law, that balance between the two? There are also some very dramatic set pieces, like the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket, at his own cathedral in Canterbury, by King Henry II. So, it is really about who will be the most important influence in a Christian kingdom, the archbishop or the king.

Organising Christianity in the 1100s

Professor of Medieval and Early Modern History

- The 12th century is an important period, because there’s a debate about what sort of pact should exist between Church and State.

- At the same time, scholars are trying to think of how Christian principles can penetrate the lives of individuals. Among others, the ritual of the Eucharist is born.

- There were also systems of surveillance and systems of punishment for those who did not adhere to the system.

Christianising Europe and beyond

The 12th century is a really good time to attempt to understand what Christianity meant to the people of Europe and, consequently, to the people of the whole world from the 16th century on. In the 12th century, we see, as we always see with historical processes, dependence on what came before, but also some very interesting new trends.

So, what did Christian Europe look like, in this period? In the centre of Europe – in parts of what are Germany and France today, and bits of Italy, even – we have the Holy Roman Empire. We have some dynastic kingdoms, like England, France, Hungary and Poland, and we have in Iberia, very interestingly, still mostly controlled by Muslim emirates. Christians are increasingly conquering areas that they then control, with large minorities of Jews and Christians living under Christian rule.

By the 12th century, most of Scandinavia is Christian, and in the 12th century there are initiatives to continue a Christianisation of Prussia eastwards, and into the Baltic.

The archbishop, or the king?

The 12th century is extremely important because it's a period in which a lot of the aspirations of the century before were realised. In the 11th century in particular, there began some movements for revisiting a tradition of a thousand years, in terms of the life of monasteries, of the roles of the papacy, and asking questions about what sort of pact should exist between Church and State, between bishops in territories and the secular rulers of those territories.

Photo by Adriano Sabatucci

Spreading Christian principles

At the same time, in the centres of learning in Europe – and Paris is the centre for a theological discussion, at this time – scholars are trying to think how to envisage a Christian society, a ‘Societas Cristiana’. That is to say, how they can envisage the penetration of Christian principles not only in centres of religious perfection, like monasteries, cathedrals, collegiate churches or within the papal court, but in the lives of individuals. A great project of pastoral care – literally, caring for those sheep of the church, every believer – develops, and that means top intellectuals engaging not just in complicated theological debate, but also in handbooks, guidebooks and materials that could be used to make Christians not just something you are born into, but something that you experience from cradle to grave in a very meaningful way.

The 12th century, for example, is when the papacy and the lawyers that articulated church law, the canon lawyers, decided on what a Christian marriage is. This is the century when the list of the seven sacraments of the church, from baptism at birth to extreme unction on your deathbed, were finalised. It is then that they became something that every Christian had the right to experience.

A new ritual: the Eucharist

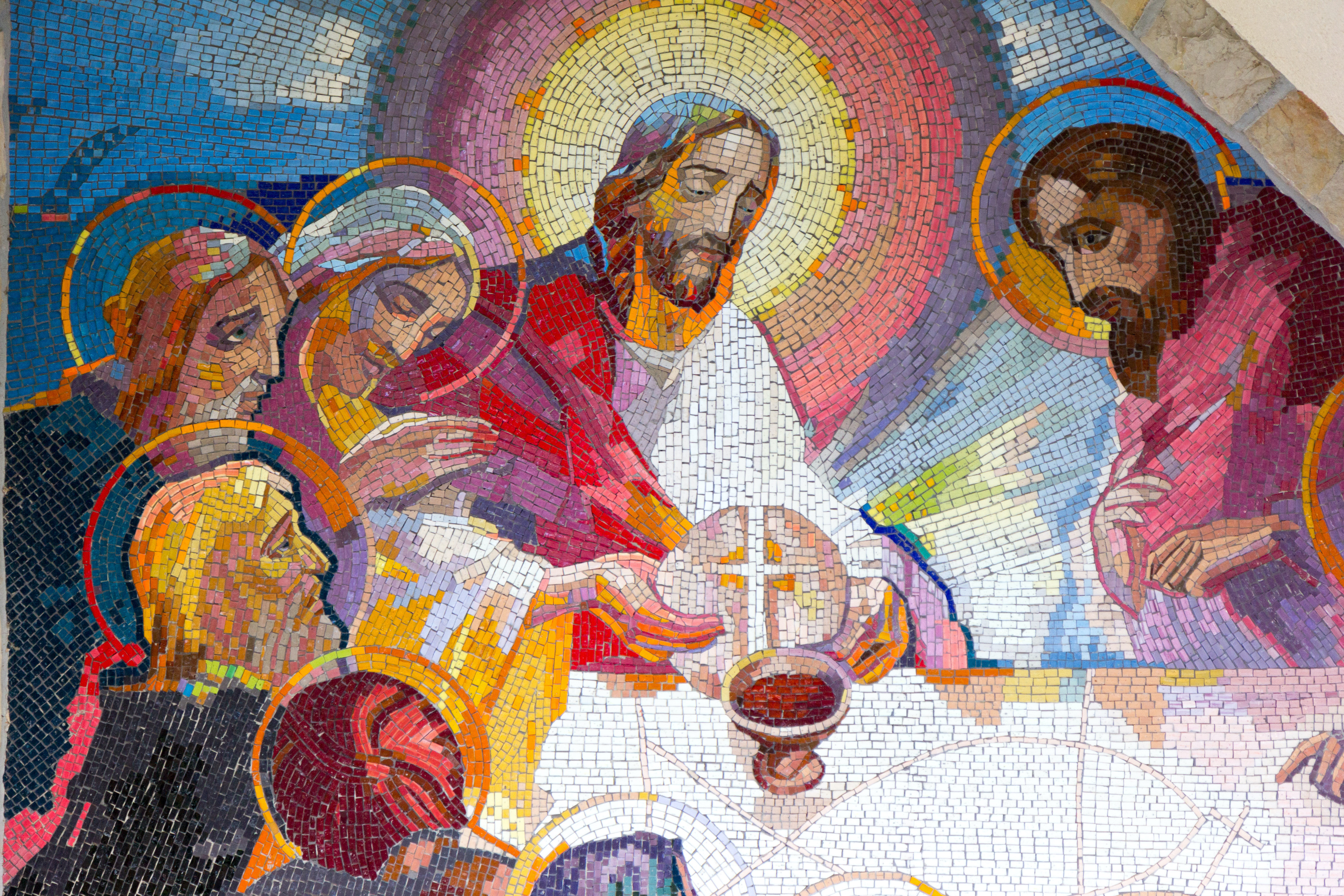

This is also the period when one of the core rituals of Christianity was enhanced in totally new ways, and that is the sacrament of the altar, the Eucharist, the sacrament that commemorates Christ's Last Supper when he gestured at the bread and the wine of the Paschal meal, and he said, ‘do this in remembrance of me’, and from that developed the sacrament of the altar. What's really dramatic in the 12th century, particularly by the end of the 12th century, is that this sacrament became the heart of Christian life for every Christian anywhere, from Krakow to Cambridge, from Lund to Livorno. Wherever they are in their parish, they will experience this sacrament.

Photo by Adam Jan Figel.

A few decades later, in 1215, it was decided that every Christian should do it once a year. But the interesting thing about this ritual is that within it, is enfolded the whole Christian story about a God who was incarnated. That is, he took on flesh and blood, but also died on the cross. He then, of course, was resurrected, and left this memory for every single believer. What's extraordinary is that, if you can believe it, it allows every Christian to have the most extraordinary, intimate contact with Christ, literally at the altar, at communion, to receive what looks innocently like a piece of baked dough, but, in fact, is Christ's body through a very complicated and challenging process known as transubstantiation, the changing of the substance of the bread and the wine at the altar by the priest’s consecration and Christ's real, historic, saving body.

Systems of surveillance

Alongside this blueprint for the Christian life, for millions of European Christians there were also systems of surveillance, systems of punishment, systems of eking out, seeking out, and investigating and punishing those who did not adhere to the system or challenged it quite openly.

Some scholars even talk of the 12th century as a period when a persecuting society developed alongside the efforts to inculcate in more peaceful ways. One might even say that the sacraments themselves had built-in modes of self-discipline. Think, for example, of confession. Confession is about self-scrutiny. It's about self-examination as well as the relief after confession of doing some penance and returning, as it were, to the fold. Indeed, if you received the sacrament of the Eucharist without truly believing in its theological tenet, it would do harm rather than good.

So, alongside these demands from Christians as to what to believe and how to adhere, there were systems of surveillance. Bishops depended on local parish priests to report cases that did not just respond to gentle admonishing and correction. Even neighbours were encouraged to inform on their own neighbours, if they found them to be living less than a good Christian life.

What happened to those who did not comply?

Those who would not listen, would not be corrected, who absolutely and publicly denied the very underpinnings of the system, were deemed to be heretical. Heretics were dealt with in various ways. Bishops ran courts which tried them, but in those areas where there seemed to be a particular concentration of challenges to the church and where organised local religious sentiment that could not be allowed to exist alongside the Catholic Church, like the Cathar civilisation, the Papacy organised particular treatment. That's how we get the papal inquisition, which comes into place in the early 13th century.

Photo by Vuk Kostic.

The Papal Inquisition were professionals, particularly trained, particularly educated, and usually members of the Dominican order. This order offered itself for the service of the Papacy and the extirpation of challenges to it, like heresy. These were very learned people. They became specialist interrogators and they went out to these areas. When preaching did not suffice, the Papacy was able to combine with secular rulers like King Louis IX of France who, with knights from northern France, organised into a crusade on behalf of the Papacy, in order to destroy the communities who had challenged the Catholic Church.

The role of the arts

All the work of making Christianity for people, of teaching it, made use of all the senses. It made use of sound, of visual cues, of material culture and of music. The liturgy of the Church – that is, the worship of the church – even if parishioners just listen in, is nonetheless a celebration in the sound of every parish church. Even the most modest ones had certain elements of decoration that were didactic, with the purpose of enhancing the belief that we're being taught also in words from the pulpit.

Almost every English church, for example, had a doom – a great painting of hell and the last judgment – right where the parishioners looked up towards the east, towards the chancel where the priests celebrated the sacraments. In French churches in the 12th century, there develops the most wonderful type of simple wood-carved, painted Madonna, to tell the story of incarnation and hope for salvation through the Virgin Mary. This material culture is also very regionally diverse. In some areas, it's statues in stone, in some it’s in wood.

Virgin and Child in Majesty. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Discover more about

Christianity in the 12th century

Rubin, M. (2020). Cities of Strangers: Making Lives in Medieval Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Rubin, M. (1999). Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews. Yale University Press.