The next major breakthrough came several decades later, in 1911, when Ernest Rutherford (who had been one of Thomson’s PhD students in the late 1890s) was working at the University of Manchester. Rutherford and his researchers Geiger and Marsden did this very famous experiment where they fired alpha particles, a type of radiation emitted by certain radioactive elements, at a thin gold foil. They discovered something very strange, which is that these alpha particles act like high-velocity bullets. You can imagine them as shells from a cannon being fired at gold atoms. Rutherford was surprised to discover that these alpha particles were occasionally getting knocked backward off the gold foil. This led him to realise that atoms have a tiny, extremely dense centre, which we call the nucleus. The nucleus, which is positively charged, contains almost all the atom’s mass, and the electrons go around it. What was happening in this experiment was that these alpha particles were occasionally coming really close to this tiny nucleus. And when they got really close, this enormous positive charge repelled them backward.

The basic building blocks of our universe

Particle Physicist

- Pioneering scientists like Thomson and Rutherford used basic equipment to make ground-breaking discoveries such as identifying electrons and the nucleus of the atom.

- Since the 1960s, scientists have used huge accelerators to create high-energy collisions between particles, which led to the discovery of quarks.

- The Standard Model explains how these particles interact with one another and is one of the crowning intellectual achievements in human history.

- The framework of quantum field theory allows us to understand the forces of nature, or at least three of the forces of nature.

The particle pioneers

Looking at the history of particle physics is a good way to understand what we currently know about the basic building blocks of our universe.

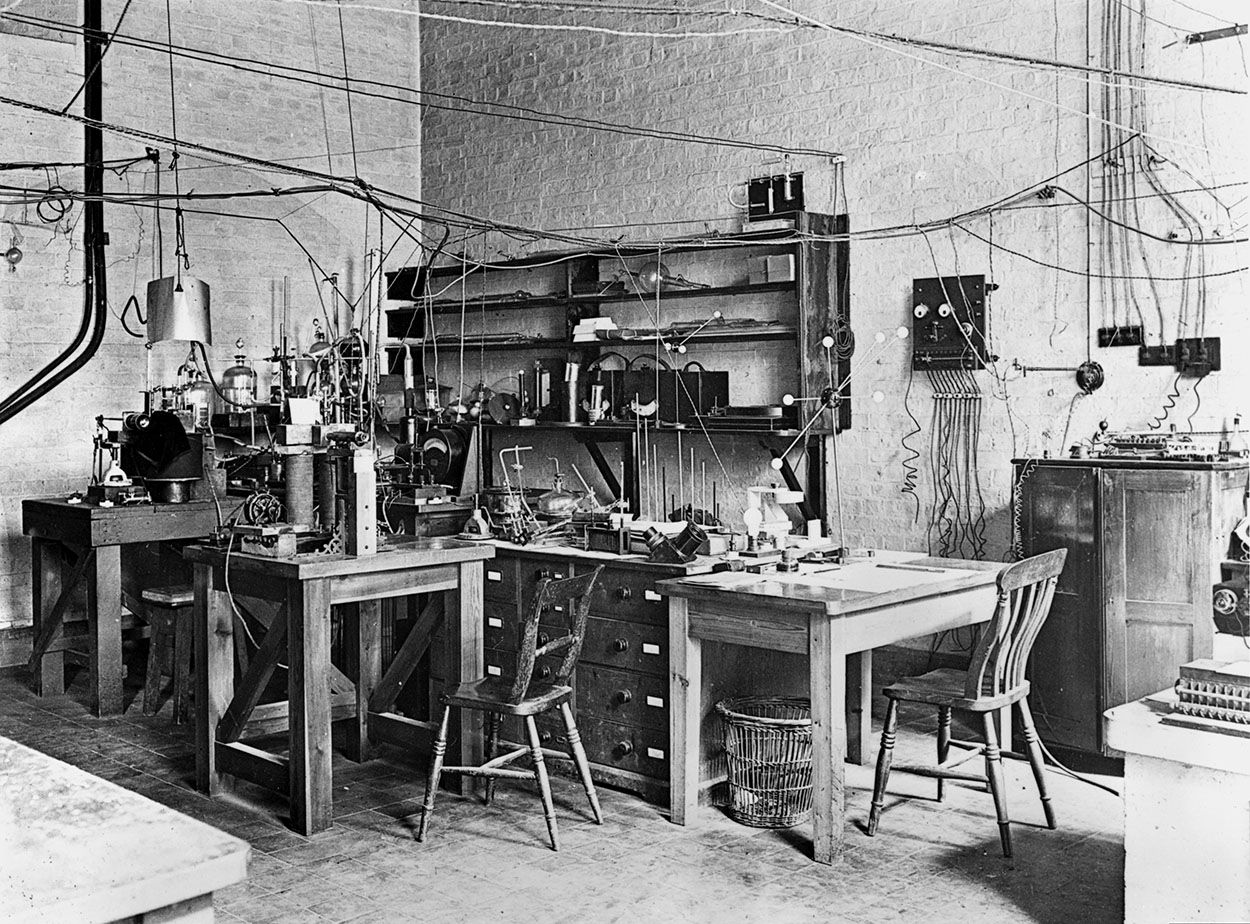

The story starts in 1897 at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, where I’m based. A scientist named Joseph John Thomson discovered the first elementary particle: the electron. His experiment used basic equipment — a glass tube pumped out of all the air through which he just passed an electric current. By manipulating these beams of particles, Thomson figured out that what was flowing through the tube were particles much lighter than the lightest known atom at the time. That’s what we now call the electron – the first elementary particle; a tiny, negatively charged particle. 1897 is really the beginning of a journey of exploration, as other scientists start to gradually unpick and dismantle the atom over the next half-century or so.

The apparatus used by Ernest Rutherford in his atom-splitting experiments, set up on a small table in the centre of his Cambridge University research room – Cavendish Laboratory. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The quest for quarks

Over the next couple of decades, scientists discovered that the nucleus is made of even smaller particles called protons and neutrons. The proton is positively charged; the neutron is electrically neutral. This is an amazing achievement because, with the proton, the neutron and the electron, you can now understand all the elements from hydrogen through to uranium, in terms of their chemical properties determined by the number of protons in the nucleus. Hydrogen has one proton, helium has two and so on. With this simple model of three particles, you can assemble all of the chemical elements in nature and begin to understand their properties.

But that’s not the end of the story. In the 1960s, scientists realised that the proton and neutron themselves, thought to be the fundamental building blocks of the atom, are actually made of even smaller particles called quarks. This is discovered using a giant particle accelerator.

So, over around 60 years, we’ve gone from a little tabletop experiment in a lab in Cambridge to a particle accelerator three kilometres long near San Francisco, so big it was nicknamed “the monster”. What this accelerator does is act as a kind of electron gun. It fires electrons at very close to the speed of light and bangs them into protons. By looking at how the electrons get scattered by the protons, scientists realised that there are three smaller particles inside the proton. These are the things that we now know as quarks.

From photons to bosons

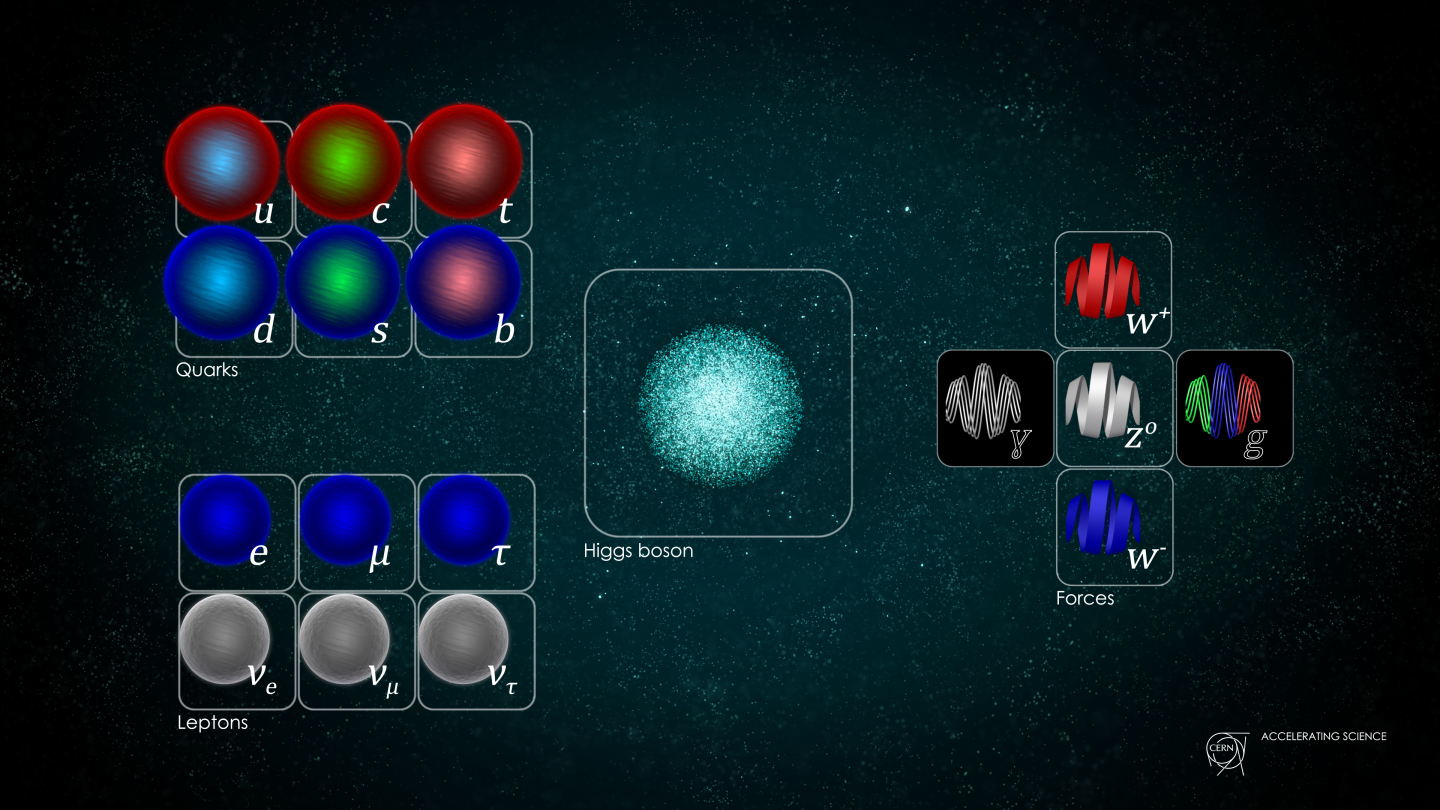

By the 1960s, we have this really simple model of what the universe is made from. Electrons go round the outside of the atom, and in the nucleus, you have quarks. There are two types of quarks: one is called the up quark, which is positively charged, and the other is called the down quark.

It’s a radically simple picture of matter, but it’s not the whole picture. These three particles – the electron and the two quarks – make up physical matter in the world around us. But there’s another set of particles that are associated with the forces of nature. These other particles allow the matter particles to interact with one another and form atoms.

The most familiar of these is the photon, the particle associated with light and electromagnetic force. That’s the force that holds the electron in orbit around the atom. It’s the attraction between the negative charge of the electron and the positive charge in the nucleus.

The two other fundamental forces in our current theory of particle physics are the strong force and the weak force. The strong force binds the nucleus together; in particular, it holds the quarks together inside protons and neutrons. Associated with the strong force are particles called gluons. Quite literally, they glue the quarks together. On the other hand, the weak force isn’t like electromagnetism or the strong force, in the sense that it doesn’t actually stick particles together. Rather, this force allows particles to change from one type into another. It’s responsible for many types of radioactive decay, where an atom transforms into a different sort of atom.

Super Proton Synchrotron. Courtesy of CERN PhotoLab Archive.

The weak force has two particles called the W and Z bosons. These were discovered at CERN in the 1980s using the predecessor to the machine that I work on, a big particle accelerator called the Super Proton Synchrotron, which smashed protons and antiprotons together with lots of energy. It produced these W and Z particles in those collisions.

That’s really the whole of particle physics, with one exception that was discovered relatively recently at the Large Hadron Collider – the Higgs boson.

Boring name, brilliant idea

The Standard Model is a boring name for probably the most impressive intellectual achievement in human history. It’s a highly mathematical description of how all these different particles interact with one another. It’s written in a language, or framework, known as quantum field theory, which is an amalgam of two of the most revolutionary ideas in 20th century physics: Einstein’s theory of relativity, which describes how objects behave when they’re travelling very close to the speed of light, and quantum mechanics, the language used to describe how elementary particles behave.

The Standard Model. Courtesy of CERN PhotoLab.

Famously, the laws of quantum mechanics are counterintuitive. They tell us the universe isn’t deterministic, and that you can’t know precisely how a particle or system will behave. You can only know the probability that it will behave in a certain way.

When you bring these two very powerful ideas together, you eventually arrive at quantum field theory, which describes how all these particles interact and behave.

A strange but beautiful idea

The way I’ve described particles so far, you might be picturing them as tiny spheres, like marbles, but quantum field theory suggests something much stranger: particles are not the universe’s fundamental building blocks. The fundamental building blocks of the universe are much less tangible objects called fields.

A field is a fluid-like substance that fills all of space. We’ve all encountered fields. If you’ve ever held a magnet next to a piece of metal and felt a force on that piece of metal at a distance, that’s due to something called a magnetic field. Quantum field theory says that every particle is a little ripple moving through an associated quantum field. An electron is a ripple in the electron field. The photon is a ripple in the photon field (also known as the electromagnetic field), and so on. The material universe and everything that exists is made out of these fields. The particles are manifestations of those underlying fields, which is a strange but rather beautiful idea.

A symmetrical universe?

This framework of quantum field theory allows us to understand the forces of nature, or at least three of the forces of nature.

Space background with two symmetrical twins spiral galaxy and stars. Elements of this image furnished by NASA. Photo by Elena11.

The Standard Model contains three quantum forces: electromagnetism, the weak force and the strong force. There’s a fourth force, gravity, which is not part of our picture of particle physics. That’s one of the outstanding problems in theoretical physics.

Let’s take the electromagnetic force, which ultimately seems to arise because of symmetries in the laws of nature. When you construct the theory of electromagnetism in the Standard Model, the starting point is to say that the universe possesses a certain kind of symmetry. It’s a rather abstract sort of symmetry, but it’s not a million miles away from the kind of geometrical symmetry with which we’re more familiar. A square, for example, has symmetry. You can rotate it 90, 180 or 270 degrees and it will look the same. There’s a comparable kind of symmetry which we believe is responsible for creating the electromagnetic force.

The theories of these forces are fantastically powerful. The theory of the electromagnetic force, for example, tells us how electrons and photons interact with one another. It’s arguably the most successful scientific theory ever written down. You can make predictions using this theory to about 1 part in 10 billion. This is why I say that the Standard Model is one of the crowning intellectual achievements in human history. It describes almost everything that we know in the world around us, and it does so incredibly precisely.

This reductionist approach to nature – breaking matter down, looking at smaller components, studying how those things behave and so on – has taught us a tremendous amount about the world around us. It’s a powerful way of understanding nature.

Discover more about

the particle physics revolution

Cliff, H. (2021). How to Make an Apple Pie from Scratch: In Search of the Recipe for Our Universe. Picador.