Post-war ideals and the political aftermath of World War II

Writer and Professor

- The end of WWII led to a new order set up by the allies, particularly the Americans aided by the British.

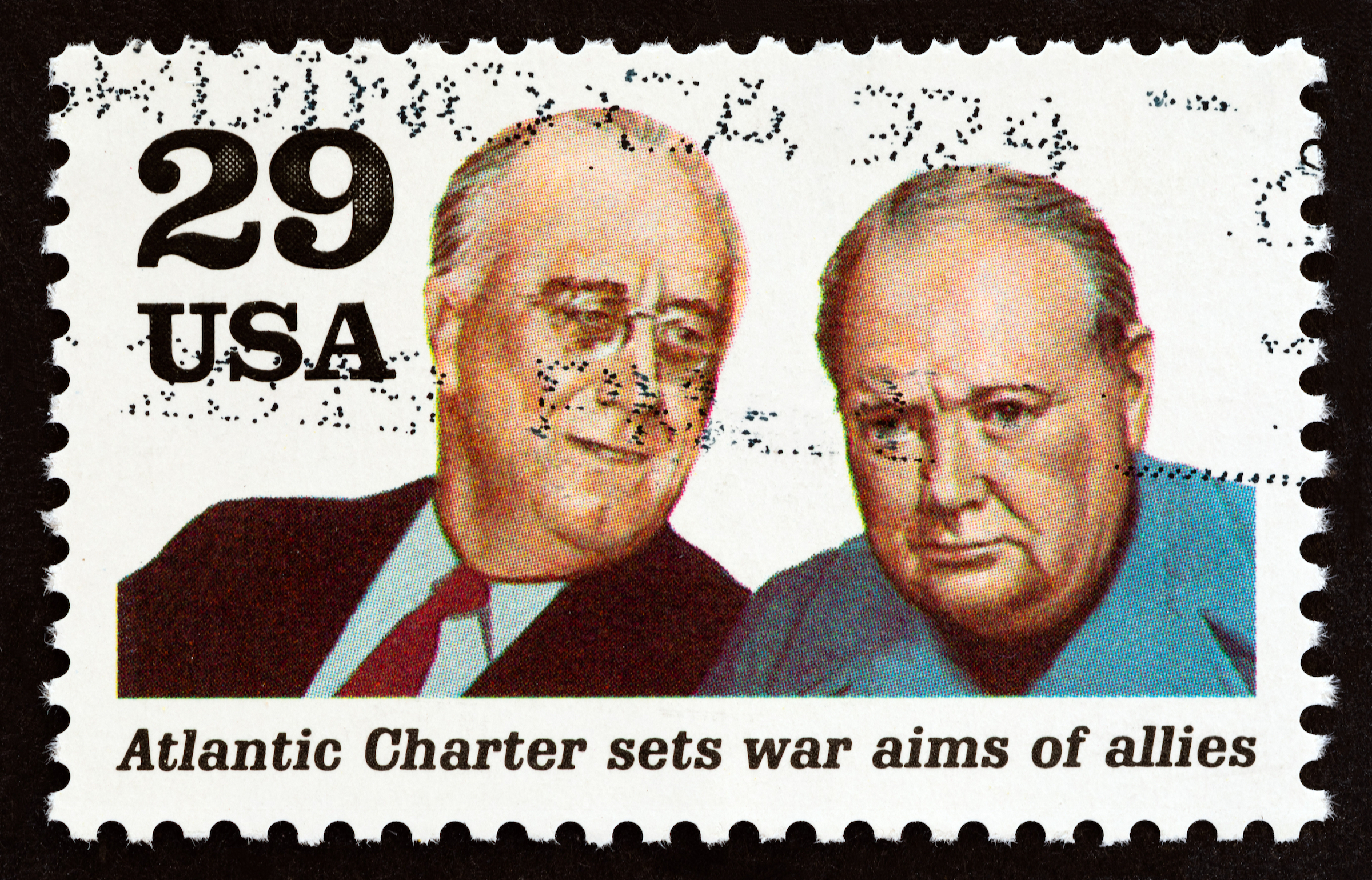

- The Atlantic Charter was a blueprint for what the Anglo-Saxon allies thought that the post-war world should look like. It stressed international cooperation, political freedom and national independence.

- When the Soviet Empire collapsed, the ideology of individual freedom, of less collectivism, of no more effort to redistribute wealth became the prevailing dogma.

- After WWII, the European empires that had been built over several centuries gradually came to an end.

The new order

The question is whether a new free world emerged from the carnage and the horrors of WWII. Clearly, not in many parts of the world. Eastern Europe and Central Europe were less free than they had been before the war. China was not free. North Korea wasn’t free. There are many countries that ended the war with less freedom than they had before. But you could say that it did lead, in large, important parts of the world to a new order set up by the allies, particularly the Americans aided by the British. That was better than the arrangements we’d had before WWII. The history of it started before the United States joined the war, in 1941, when the majority of the population in the United States was still against joining the British in the war in Europe. People always forget this. Tony Blair, famously, in the run-up to the Iraq war, told an American audience that the reason for Britain to stand by George W. Bush in the Iraq war was that only one nation had stood by shoulder to shoulder with the British in their hour of peril in 1940, and that was the United States of America. This was false. The United States of America did not join the war until it was attacked by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor.

Nonetheless, Franklin D. Roosevelt did not want Britain to go down, and helped them in various ways, though was still very loath to join the war formally. Churchill was desperate for the Americans to join. Finally, Churchill got his wish and met Roosevelt in person in a bay of Newfoundland, Canada. Roosevelt had gone there under false pretenses: he pretended to go on a holiday trip on his yacht and was then put on a battleship which met the British in neutral ground. There, amongst a lot of pomp and ceremony and singing of hymns, they devised the Atlantic Charter 1941. The Atlantic Charter was not a treaty: it was more an agreement of intent. It was a blueprint for what the Anglo-Saxon allies thought that the post-war world should look like. It stressed international cooperation, and the desirability for international institutions, for economic cooperation, for political freedom and national independence. This was somewhat of a sticking point between the British and the Americans, because the Americans very much saw the United States as the defender of national independence, as the anti-imperialist power. Roosevelt was not at all keen on the British Empire. Churchill, on the other hand, was extremely keen – for sentimental reasons, but also because he realised that without the empire Britain would very quickly be relegated to a far more minor status in the world. So, when Roosevelt suggested in the charter that people should be able to choose to be independent, Churchill said that it should only apply to countries that were now under German occupation, and certainly not to the nations who were part of the British Empire. Roosevelt did not like this, but gave in in order for the two countries to continue having close relations.

The birth of the UN

Photo by Alexandros Michialidis

When the war was finally over, this blueprint started getting real teeth. The United Nations, which had been the officially designated name for the allies who fought Germany and Japan, became a formal project, although quite what the United Nations would become, they couldn’t entirely agree on. The Soviet Union wanted it to be a fig leaf for a world run but divided between the Soviets and the Americans, who would then run their own spheres and use the United Nations as a convenience. This is, of course, not how most smaller nations who were dependent on either of these powers saw things, but the United Nations certainly came out of the ideals of the Atlantic Charter, as did the IMF, the World Bank and even the idea of a unified Europe. Churchill was one of the first promoters of that idea, in the famous speech he gave in Zurich soon after the war: he said that the only way for Europe to be secure in the future would be for it to unify. Coming from Churchill, this sounded unusual, but it wasn’t entirely: in the very beginning of the war, just before France was defeated, Churchill was even receptive to the notion of uniting France and Britain into one country.

What Churchill didn’t spell out was what Britain’s role would be in this united Europe. He talked about Britain being a benign patron but he still thought of it in terms of the British Empire, as a sponsor of the project and not a participant on equal terms with the Germans, the French, the Italians and others. How could it be equal? Britain had won the war and these countries had either been defeated and had been under occupation, or were guilty. This is how most British people saw things in those days, and how some British people still do.

The unification of Europe

In any case, without the British, Europe did begin to unify – first in the Coal and Steel Community, then in the European Economic Community. The French tended to dominate because the Germans didn’t want to play a leading role after what had happened during the war. So, for them, it was convenient not to be German, but to be European. The French, especially when de Gaulle was in power, called the shots. He did not like the idea of Britain joining, and he vetoed them twice. But the British began to realise that if they were not going to be part of a united Europe or European community of any kind, they ran the risk of being isolated from America and Europe, which could do great damage.

So, these ideas of international cooperation, international institutions and an internationalist world were very strong, as was the notion, especially during the Cold War, that in order to build a world that was better, a world in which there would be no more revolutions, no more fascism, no more war, you needed to build societies that were more equal, where people were more prosperous and freer than they had been before the war.

There was a consensus for forms of social and Christian democracy that were egalitarian, even though still capitalist in the Western democratic countries. In the Cold War this was important, because the West needed a cold counter model to the communist one. However horrific life was under Stalin, the communist model still promised equality, so the Western capitalist world had to have something that they could show their people that was perhaps even better. The notion, therefore, that strong trade unions equal more egalitarian distribution of wealth, was considered to be important.

The beginning of the end

Photo by mark reinstein

This idea began to crumble a little after the economic difficulties of the 1970s. When Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan came to power, the trade unions had become very strong, perhaps too strong in countries like Britain. Margaret Thatcher promised to rein them in, to have more individual freedom to accumulate wealth, less coercion to distribute it equally, as well as Ronald Reagan, who also saw this as a form of rugged individualism. There was a lot of rhetoric on both sides of Anglo-Saxon values and individual freedom, so the notion of social democracy, of equality, of redistribution of wealth began to weaken gravely in the 1980s. Then, to everybody’s surprise, the Soviet Empire collapsed at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, which was a real watershed. This is when the post-war order set up by the Americans, the British and others began to seriously deteriorate. I believe one of the reasons was that the need for having a counter model that was also, to some extent, egalitarian, was no longer considered to be of such importance. This is when the ideology of individual freedom, of less collectivism, no more effort to redistribute wealth, to let everybody get as rich as they wanted, to have lower taxes and so on, became the prevailing dogma.

People still believed in the need for international cooperation and international institutions, although perhaps a little less than the generation that came after WWII. Memories of the war began to dim and fewer people saw that need to further integrate Europe, because otherwise there might be a risk of another world war. This was no longer taken so seriously. It was the beginning of the end of the post-war order. It hasn’t completely ended yet, but the world we’re living in now is a complete repudiation of that order set up at the end of the war. It’s more nationalist. It rejects international cooperation. Britain chose for Brexit, so it did end to some extent, I believe.

The end of European empires

Photo by Lefteris Papaulakis

One thing that came from the end of WWII was gradual, and sometimes not so gradual, ending of European empires, which in turn led to other forms of empire, some would argue. However, the European empires that had been built over several centuries gradually came to an end: the French Empire in Indochina, the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies – now Indonesia – and the British Empire in India and elsewhere. This was, to a large extent, the result of WWII, the result of the Atlantic Charter – which Roosevelt had always seen as an anti-colonial project – the result of the fact that Britain was bankrupted by WWII and could no longer afford to have an empire. One of the great fears of imperial powers was that without an empire, they’d be impoverished. The empires were the one thing that made European nations such as the Dutch or the British rich, which later historians have somewhat debunked. At that stage, empires were probably more of a drain on the finances of imperial powers than a boost. But nonetheless, the subjects of colonial empires, already at the time of the Atlantic Charter itself, had realised that this was the moment for them to assert their desire for national independence, for freedom from imperial rule. Pandit Nehru, the prime minister of independent India, very much took that view during the war and saw the Atlantic Charter as a great boost for national independence, for the freedom from imperialism.

A war of liberation?

The Japanese also had a hand in the end of the European empires. One of the arguments made by Japanese nationalists who try to justify the Japanese war in Asia is that, after all, it was a war of liberation. They were fighting the war. And this was true as far as the propaganda went and what some people clearly did believe – that the Japanese war in Southeast Asia and China and Northeast Asia was fought to liberate Asians from Western colonial rule. Asia for the Asians. Now, the fact that Western colonial rule was very quickly replaced by Japanese rule, which was in some places even harsher, is another issue. But the argument is still there. And to some extent, it is true; not that the Japanese military governments in the Dutch East Indies and Singapore and Malaysia and other places truly wanted these countries or these people to be free. They didn’t. They were very authoritarian. They broke the back of European imperial rule, if only to show that the Western imperial powers were not all powerful. The fact that they could be so easily defeated by a Japanese military force in 1941 and 1942 showed how vulnerable they were. And the one thing that is deadly to any kind of authoritarian or dictatorial or colonial power is the destruction of the image of omnipotence. After all, Britain ruled India for a long time with only a handful of British soldiers, really. The only reason that they could continue to rule was because most Indians saw this as an inevitable fate. After all, what can you do against Great Britain?

Once the Japanese showed that Great Britain was no longer so great, they could be fairly easily defeated. Their battleships could be bombed. In Singapore, they surrendered to the Japanese very quickly. And there was General Percival in his shorts and his spindly legs standing like a schoolboy in front of Japanese generals. Now, this image, of course, showed that the end could no longer be postponed for all that much longer. So the end of colonial rule was clearly one of the consequences of WWII. Whether that led to more freedom, of course, is a very different issue; very often it led to national independence, but to national dictatorships, which in some cases could be worse than being under colonial rule, which was not always completely malign after all. And then you come into questions of, well, is it better to be ruled harshly by your own people or to be ruled relatively benignly by foreigners? These are philosophical questions. But one thing is clear: that without WWII, the European empires would not have come to an end so swiftly.

Photo by Everett Collection

Different kinds of freedom

One problem with this discussion of whether the free world emerged after WWII is the concept of freedom. What do we mean by freedom? Every country, even dictatorships, tend to use the word freedom in the title of the name of their countries. There are different kinds of freedom, so it’s a very difficult question to answer. The post-war world was freer than the pre-war world: more countries were free to choose their own governments – not yet in the Soviet Empire, but eventually even there. It’s certainly true that the internationalist order that came out of WWII and the Atlantic Charter – the idea of cooperation and equality – was eroded in the 1980s, the 1990s and in the 21st century, but it does not necessarily mean that freedom came to an end. After all, even under Donald Trump, you can’t say that the American people are yet completely unfree. Even in Eastern Europe, horrible though the conservative government of Poland today is, you cannot argue that it’s as unfree as it was under communist regimes.

So I wouldn’t say that freedom has yet come to an end. This may still happen in many places, but it hasn’t yet in some way. In the 1990s, people who argued for neo-liberalism would have claimed that it makes people more free. After all, they were for more economic liberty, more individual liberty and less government intervention to redistribute wealth more equally. They would argue this was a form of expanded freedom. Logically, they’re right, but as we know from the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, different kinds of concepts of freedom can clash. Those who feel that we should pay more tax so that wealth can be more equitably distributed certainly argue for a good thing and it makes people collectively a bit more free from poverty. Those who argue that we should pay less tax because otherwise individual freedom to enrich ourselves is challenged have a certain logic, too. Those two views of freedom clash, which is only to show that one cannot simply use the word freedom loosely. It means different things to different people, and can mean different things at different times. So far in the Western world, not all freedom has yet been lost.

Discover More About

post WWII ideals

Buruma, I. (2020). The Churchill Complex: The Curse of Being Special, from Winston and FDR to Trump and Brexit. Penguin Press.

Buruma, I. (2014). Year Zero: A History of 1945. Atlantic Books.

Buruma, I. (2014). Theater of Cruelty: Art, Film, and the Shadows of War. NYRB Collections.